On June 27, 2022, James F. Keene (August 19, 1948), one of my most important mentors, passed away from acute myeloid leukemia. The onset was sudden and shocking. I got a message from Alice, his wife of 48 years, just two days before he died saying that they “were going to fight this battle aggressively.” I would’ve expected no less from either of them. In fact, it was the second time in his life that Jim Keene faced his own mortality and stared it down.

It has taken nearly a year to organize my thoughts about this amazing man, to try to process this loss, and put into words the influence he had (and still has) on my life. Whatever follows will no doubt be insufficient in achieving that goal.

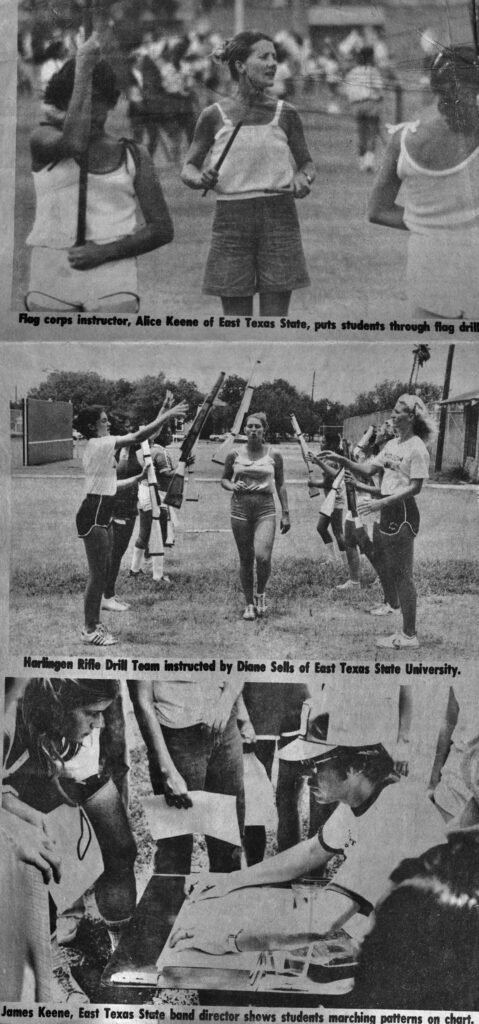

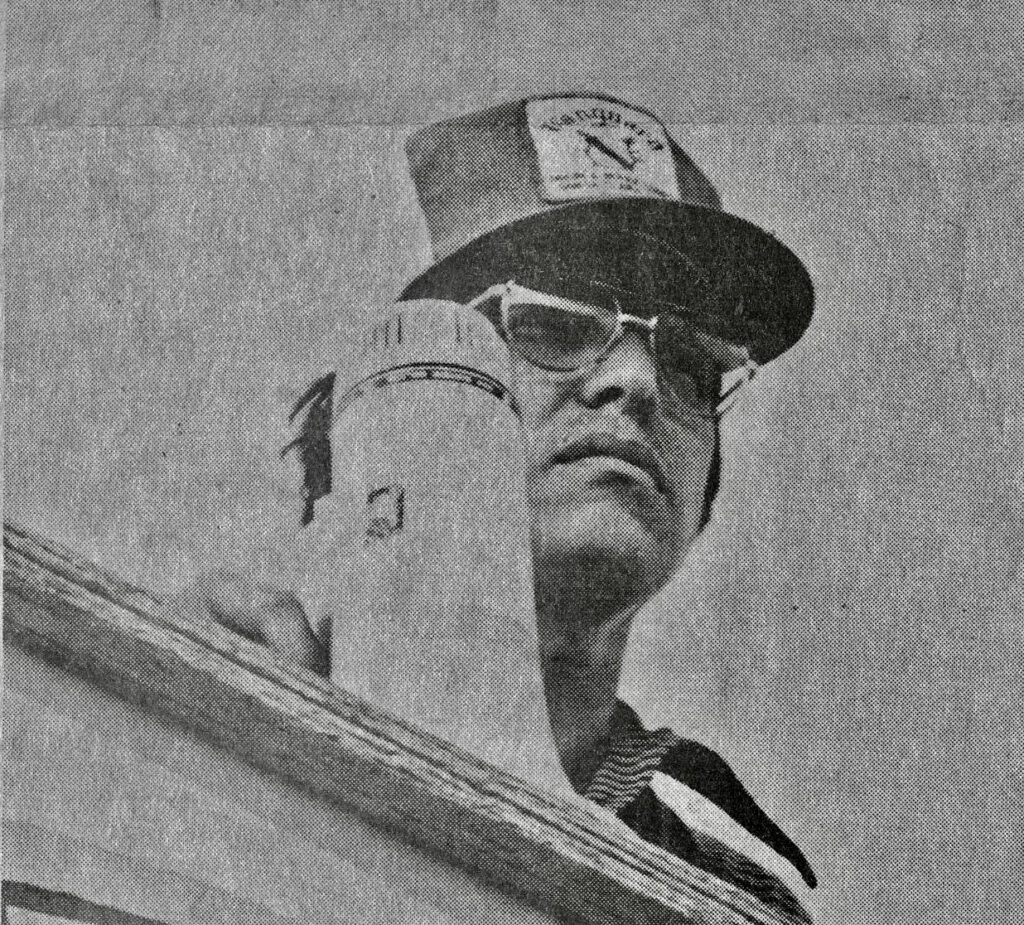

When we first met, Mr. Keene was the new Director of Bands at East Texas State University (now Texas A&M Commerce), and although his tenure at ET was just a small blip on the timeline of his journey to the top of the band world, the imprint he made on the lucky few of us in his band cannot be overstated.

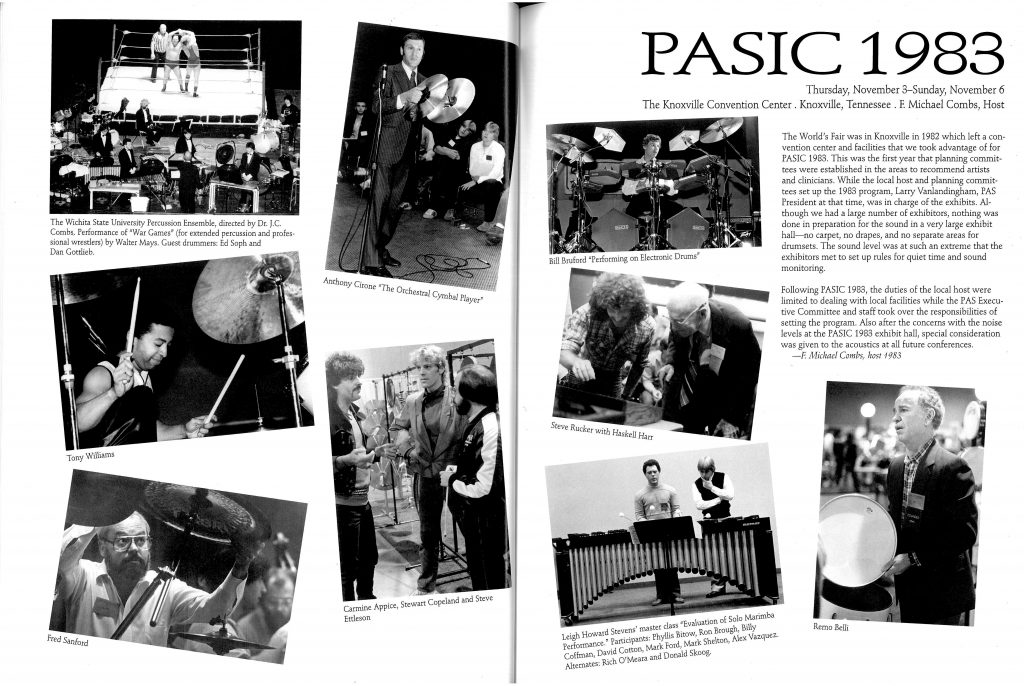

He spent just a few short years in Commerce (1975-1980), before moving on to the University of Arizona (1980-1985) and then to the University of Illinois where he became the school’s fourth Director of Bands and the Brownfield Distinguished Professor of Music (1985-2008). Even though he was with us for such a short time at ET, Keene (as most called him) is still revered and celebrated by our cadre of East Texas kids who he inspired to achieve excellence beyond anyone’s expectations (including our own).

In short, he lived a full life after leaving Texas; a life that had its share of successes and setbacks. But in the end, it was Texas where the native Michigander chose to retire. He once said to me that “at five o’clock on my last day at Illinois, the moving truck will be backed up to our house, and we are heading to Texas.” And that’s exactly what they did. He and Alice made a happy home in San Antonio that featured a putting green in the back yard, a few harps, and many visits from his two granddaughters.

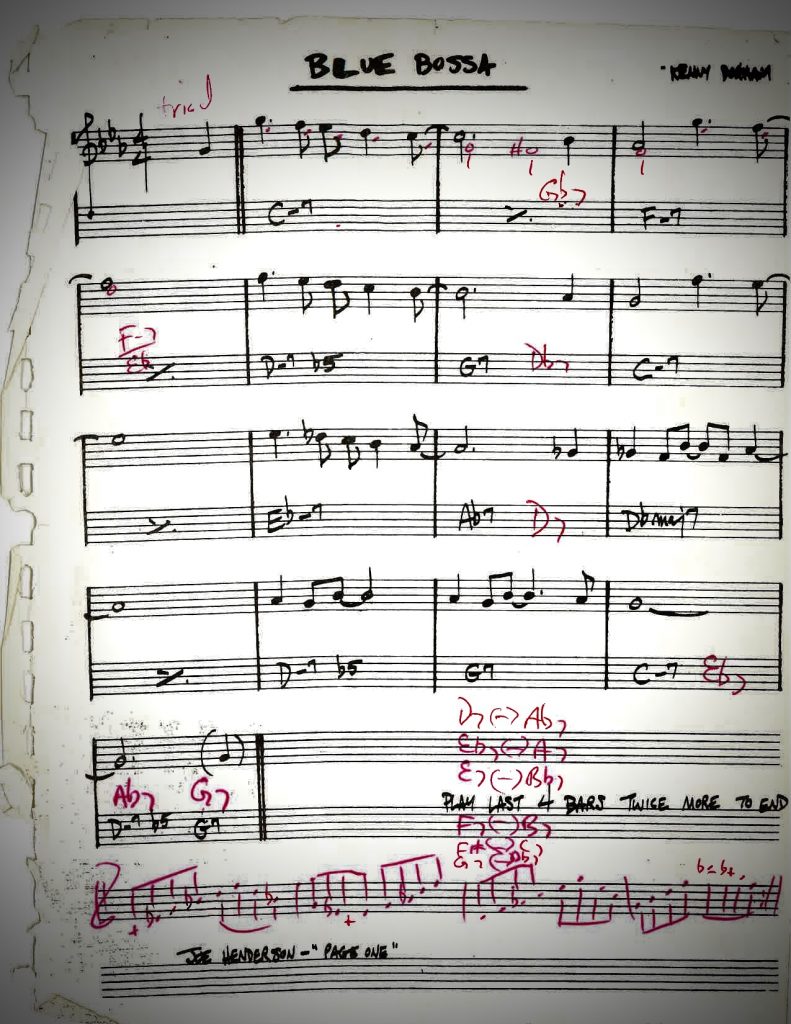

Although he spent only five years as a fulltime band director in Texas, Jim Keene had a profound impact on Texas bands. He was among the first to bring corps style marching concepts to Texas and he hosted drum corps like Phantom Regiment, the Blue Stars, and others on the East Texas campus, to rehearse and do exhibitions. The corps sought him out for his astute and candid assessment of their programs. I was fortunate that he brought me along to teach drumline and percussion at many of his marching clinics throughout Texas, often with Alice teaching colorguard, and others from his inner circle of student assistants.

As a result of his many contributions to bands in Texas, Mr. Keene became the sixth person to receive an honorary lifetime membership in the Texas Bandmasters Association (today there are 15 renowned band conductors who hold that honor). According to their website, “TBA Honorary Life Members are chosen in gratitude for a lifetime of support and service to the world of music.”

I knew James F. Keene for 46 years, 1 month, and 3 days. We met on May 24, 1976. That date stands out because it was the final concert of my senior year of high school. I was loading equipment into the Longview High School Band Van (the only transportation I had in high school), when Mr. Keene suddenly appeared at the rear door of the van, thrust his hand toward mine and said, “I need you to come to school at East Texas State University; let me know if there is anything I can do to help you.” I later came to realize that that hand shake was uncharacteristic for him, as were hugs or other physical signs of affection. He wasn’t fond of shaking hands and I don’t recall shaking his hand at any other time. He also never used the word “goodbye,” which was first pointed out to me by saxophone virtuoso and Professor of Music at the University of Michigan, Donald Sinta. He didn’t like the notion of seeing someone for the last time—relationships with him were nuanced and ongoing—it was understood that it was always “until we meet again.”

Mr. Keene was ostensibly in Longview that night to try and recruit my friend and high school classmate Lynn Childers—a talented trombonist that many schools were trying to attract. I was just a bonus because of my ability as a truck loader and (I suppose) drummer, as both skills were on display that night.

At the time, Lynn was planning a visit to Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches, and he and his dad had invited me to tag along. Lynn and I spent several summers at the SFA Summer Band Camp, and since our high school band director, John “Piccolo Pete” Kunkel—who we revered—was an SFA grad, it just seemed logical that we would go there too.

Here I was, a senior in high school with no real prospects—or even a clue—for getting into college. It was Lynn who casually asked me one day if I needed a ride to take the SAT that Saturday? I had no idea what the Scholastic Aptitude Test was, but Lynn assured me that I needed it if I intended to go to college. Who knew?

After the visit to SFA, however, we both felt that our reception there was rather cool. We thought that “maybe they didn’t need us as much as that ETSU guy,” so we planned a trip to Commerce, Texas for what turned out to be a life changing visit. Mr. Keene greeted us warmly and while Lynn visited with legendary trombone professor, Dr. Neill Humfeld, Mr. Keene escorted me to the financial aid office to begin paperwork for the Basic Equal Opportunity Grant (BEOG), now known as the Pell Grant. That grant would make it possible for me (and many of my classmates) to become a first-generation college graduate.

We were treated like honored guests, which turned out to be another of Mr. Keene’s unique talents—making people feel special. He could remember any person’s name upon hearing it once, and he had an uncanny ability to say something nice—share a little detail—about each person when introducing them to one other. We decided that day we were going to be roommates at ET. The Lions are coming.

Of course, Lynn and I weren’t the only ones to receive this treatment. There were many others—a whole band as it turns out—who were attracted to him by his sheer impulse of will.

In her groundbreaking textbook, The Modern Conductor, Elizabeth A. H. Green describes Nicolai Malko’s concept of “the will of the conductor.” She wrote; “The conductor must will certain things to happen. If he can will his hand to make the right gesture, the orchestra will read it correctly.” It has also been described as “hearing the desired sound in the inner ear, believing, and executing, thus initiating a confident response from the ensemble.”

It was clear that Mr. Keene believed in his vision for us and in his ability to execute that vision, even if he was less confident about certain aspects of his own skills. One example is that although Mr. Keene had an excellent ear, he never mounted the podium in those early days without his trusty Stroboconn model 6T-5 tuner. In the first years that I knew him, he was constantly double checking himself against the strobe. I know this for a fact because I was the one who set it up for him before every rehearsal (but that’s getting ahead of the story). In later years the tuner disappeared, as by the time he reached Illinois, his impulse of will was fully formed.

Keene was an amazing conductor from both a musical and technical standpoint. He knew how he wanted the band to sound and pursued it doggedly. I recall his impulse of will being on full display during a memorable rehearsal in which the band was struggling to execute a rhythmically challenging moment. Some sections of the band had rhythms in groupings of three while others played in groupings of two. He stopped and told one section of the ensemble to watch his left hand while everyone else was to watch his right hand, then he started again. To our amazement, he “willed” us to play the section perfectly by effortlessly executing an elegant 3 against 2 conducting pattern. When we stopped, the band spontaneously applauded him. I’ve never seen that sort of awed response to a conductor in a rehearsal before or since.

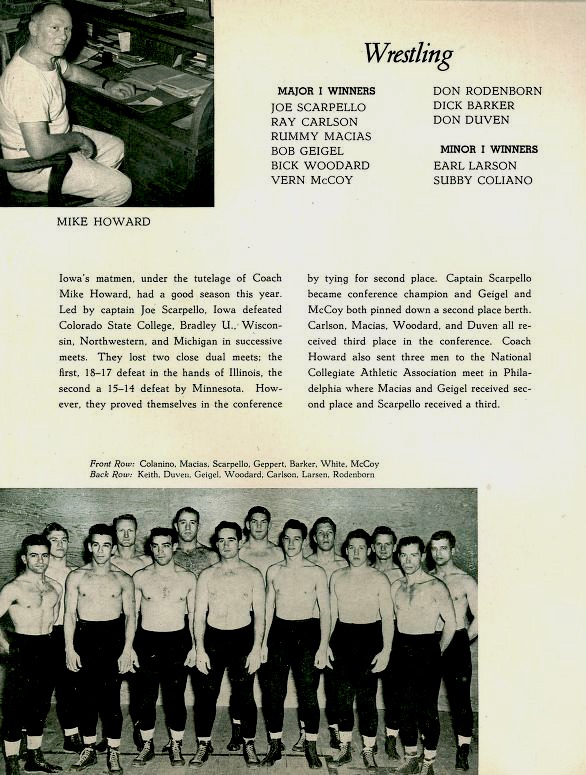

As a young man (barely 10-years older than me and many of his students), Mr. Keene could be quite charming, yet he could also be brutal and relentlessly demanding of his students and colleagues. He came to ET after completing a stint as an assistant for the mercurial band leader, William D. Revelli, at the University of Michigan. Prior to that he served as an assistant band director at the University of South Carolina (1972-73) and a year as a woodwind instructor and assistant band director at Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, LA (1971-72), but he had ambitions that would not allow him to remain at a small regional school such as ours for more than the five years it took to develop an unlikely hotbed of band activity.

From Fall 1976 until his departure from ET, I was Keene’s student, equipment manager, percussion arranger, section leader, truck driver, gopher, and (according to him) a constant source of frustration. He taught me to be organized, demanded reliability and integrity, and showed me that success and respect were privileges that had to be earned every single day. There are many stories about my experiences at ET and with Mr. Keene—some true and some apocryphal—but none that will be told here. Well, maybe one I suppose…

Whenever I would do something wrong, Keene would flash his trademark grin and say, “Daniel Moore, did your mother have any children who lived?” It broke the tension but was also a reminder that I needed to think, to do better, to be better. He teased me with it many times over the years, and I can even remember the last time he asked me that question (well, one of the last times). I was probably 40 years old and a fellow professor of music at a Big-10 university, with a DMA in percussion, and he was introducing me—on the megaphone—to the entire University of Illinois Marching Band! Thanks Mr. Keene!

Among many other things, Mr. Keene is credited with bringing the love of my life from Arkansas to Texas, for which he was quite proud. He was also rather fond of reminding me that if not for him, I might’ve ended up working at a gas station in deep East Texas, or worse—in prison. It was always tough love from Mr. Keene—the kind that cannot be meted out today—but genuine love none the less.

The last time we were together, Keene shared his concern about some short-term memory loss, and he told me of his experience with a recent memory test. It made him feel anxious and without control over the situation. For him, this was a feeling that he was unaccustomed to, and that he did not like. I had seen some of those memory slips, but at the same time, he could still remember the name of “that kid from Mesquite who played bass clarinet in the ET band in 1977.”

We had a nice lunch that day and when he picked up the check, I said “you don’t need to do that.” His response was delivered in the trademark gruff tone that instantly transported me back to 1976; “don’t tell me what I can do Daniel P. Moore!”

Well, I guess “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” to quote Mr. Keene. In fact, there are many famous quotations from Mr. Keene that live rent-free in my brain to this day, such as: “I suspicion, that you are playing a wrong note,” “what’s a half-step between friends?” “that band can’t play Come to Jesus in double dotted whole notes,” “you turkey,” and of course “it’s a Beautiful Day in Commerce.” (The ironic version).

I am thankful that I had the opportunity to tell him how much he meant to me, both in person and in writing over the years. As a young man, I once wrote him a letter that said (as near as I can recall) “I appreciate you now for all the times I hated you most.” The fact is that I never really hated Mr. Keene. What I was trying so inelegantly to say was that he saw through me and cared enough to tell me the cold hard truth about myself, and sometimes that smarted. He had high expectations for me and was disappointed when I didn’t reach them. As an adult, I loved him for his candor, his loyalty, his advice, and for setting me on the path to responsibility and success. But most of all I owe him for altering the course of my life by means of his impulse of will.

It was an honor to be part of Mr. Keene’s memorable East Texas blip. He will be missed.

Student and mentor 2015.

Citations:

Contributors, Texas Bandmasters Association, Honorary Life Members

The Modern Conductor (7th Edition), Elizabeth A. H. Green & Mark Gibson, published by Pearson, 2003

ISBN 10: 0131826565ISBN 13: 9780131826564

Contributors, Jim Cathey’s Crap. Stoboconn