If you read my post James F. Keene and the Impulse of Will you would know the influence that renowned band conductor James F. Keene had on my life and career. If you didn’t read that post before arriving here, I suggest you start there. It took nearly a year of my life before I could write about the impact of his loss or even talk to anyone about it.

It is unfortunate that it is only after the loss of a beloved mentor that one can begin to fully understand the effect that person had on the lives of others. I knew a lot about Jim Keene—perhaps more than most—but like so many things, I didn’t know enough.

A few weeks after that first post, I received an email that began:

“Dr. Moore: It was by chance that yesterday afternoon I read, and was profoundly moved by, your May 2023 tribute to our precious friend, whom you referred to throughout as ‘Mr. Keene.’”

“Clearly you knew him as Mr. Keene, probably also as Prof. Keene, Jim, and possibly at times as JFK. It is a circle of undergraduate friends on behalf of whom I presumptuously send you this message, and I invite you to take a moment to enjoy learning of yet another name by which your mentor was affectionately, and respectfully, known—Harv.”

Harv? I had heard many nicknames for Mr. Keene—mostly perpetrated by my erstwhile classmates—but Harv was not among them. The email gave a few more details but seemed somehow suspicious to me so I asked Mrs. Keene if she knew the author of the email, David C. Devendorf. Alice responded quickly that David was one of Mr. Keene’s cherished college classmates. OK, now I’m really interested.

David continued; “Any adolescent male worth his salt growing up in southeastern Michigan in the 1950s and early 1960s was, to some degree, a fan of the Detroit Tigers, and their All-Star shortstop/right fielder, Harvey Kuenn (importantly, pronounced ‘keene’). Late in 1960 Harvey was traded by the Tigers to the Cleveland Indians for Rocky Colavito; a trade which the Indians’ General Manager famously defended to the media as a trade of hamburger in exchange for steak.”

I learned from David that Jim Keene “grew up on the west side of Detroit working modestly throughout his adolescence as a caddie at Western Golf and Country Club, where eventually he was rewarded with a coveted Evans Scholar Caddie Scholarship to the University of Michigan.”

According to David, “it was thus a forgone conclusion that when, as a freshman in August of 1966, your mentor set foot in the Evans Scholar House on the Michigan campus he immediately became known to his fellow Evans Scholar brethren as ‘Harv’. Although nicknames were an Evans Scholar tradition, we all gradually outgrew that juvenile convention—except for Harv. It was his view that he was ‘steak’; and he preferred to retain his nickname, while the rest of us ‘hamburgers’ could choose to shed ours. It was for that reason that your ‘Mr. Keene’ was, for more than 50 years, known as ‘Harv’ to all of us fellow former caddies.”

As a youngster, Keene was also a musician who, no doubt, hoped one day to become a high school band director with a Bachelor of Music Education degree from the University of Michigan.

For most of my adult life I knew two things about Mr. Keene: he loved the game of golf and that he—through considerable effort—made certain that I was financially supported throughout my undergraduate degree. I was about to learn why he spent his entire career making sure that motivated students were supported regardless of their socioeconomic background because he was given that same opportunity through the Evans Caddie Scholarship. He was always trying to pay it forward.

If you don’t know, The Evans Scholarship is a full housing and tuition college scholarship awarded to golf caddies with limited financial means. In 2023, more than one-thousand Evans Scholars were enrolled in 24 leading universities nationwide including the University of Iowa where I have been teaching since 1996. I had never heard of it and had no clue, but here it was on my own campus with a new Evans Scholar House scheduled to open in 2025. Evans Scholars are selected because of a strong caddie record, excellent grades, outstanding character, and demonstrated financial need.

David challenged me to “Imagine 50 underfunded caddies as undergraduates sharing an undersized house on the Michigan campus. That may provide you with a better understanding of the source of the character that our Harv was, and the strength of character that he possessed. Harv was my Evans Scholar ‘Big Brother’ when I was a freshman, and eventually he and I were roommates in what we affectionately (and accurately) called the ‘caddie shack.’”

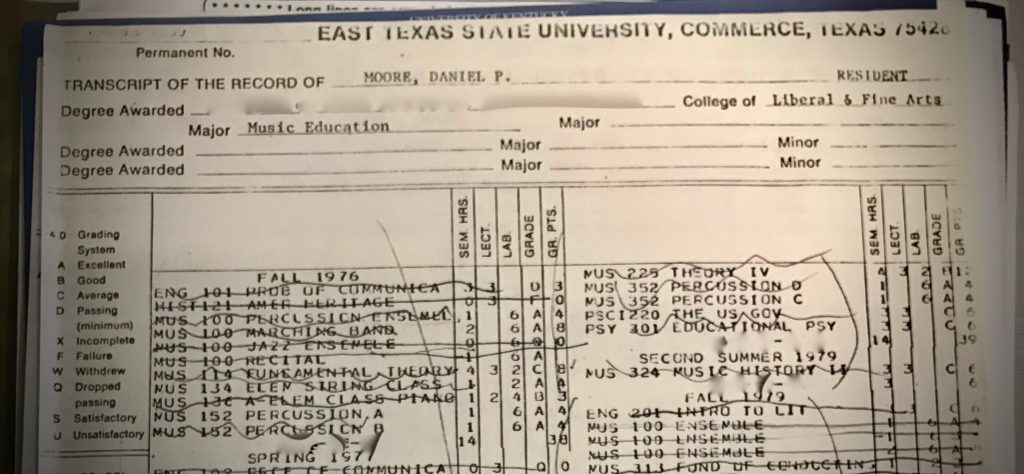

The mental image of Mr. Keene as a frightened college freshman stepping into the Evans house for the first time wondering if he would ever be able to see his education completed is powerful to me. I now know that he must’ve felt the same way in 1966 that I did in 1976 upon my arrival at East Texas State University—underfunded and scared. It is difficult to imagine him in that state but now it all makes sense.

There were several other people copied on the message that I received. When I asked about them, David told me laughingly that they were the ones who “knew where the bodies were buried.” He told me that my description of Mr. Keene resonated with their group of friends and former classmates especially in Keene’s question to me wondering if “my mother had any children who lived.” He said that “was classic Harv, and it caused me to weep when I read it. That admonition to you continues to ring in my ears this morning.” Mine too; mine too.

The email went on to say that Harv (er, Mr. Keene) was fond of referring to his classmates “sardonically as his group of ‘doctors, lawyers, and captains of industry.’ We are confident that you will understand that as well.” Indeed, I did but suspected there was more to the story.

I’ve learned over the years that many of Keene’s students, closest friends, and colleagues were subjected to the same satiric and acerbic wit. In one example I can recall adjudicating at the University of Illinois Marching Band Competition and hearing a story told by a well-respected Texas Band Director who said that he first met Keene when he brought him in to work with his high school band.

During the clinic Mr. Keene was his usual self with high expectations for this excellent High School Band. He also had some sharp criticism for the director. At the end of the session, Keene was animated and happy and suggested that they go for a celebratory dinner. The director, on the other hand, was “a wreck” after his band was “shredded by Mr. Keene,” and nearly declined the invitation because he felt he “needed to go and somehow fix his clarinet section.” We laughed about it that night with Keene sitting only a few tables away—all of us still good friends with the terrible Mr. Keene.

It is important to understand that everything Mr. Keene did or said came from a place of love even if it wasn’t apparent to the recipient of his ire at the time of its delivery. I recognized that many years ago and I’m glad that I had the time (and took the opportunity) to thank him for all of it.

Alice wrote that “Jim was committed to experiencing and appreciating history and the best of whatever subject he was into. Cooking, golf, or travel wasn’t about doing it to brag. He was eager to learn about something and personally experience it. Many times, we would say to each other that our lives were full of wonderful experiences—more than we could have possibly dreamed of. We worked hard but also were so blessed. Our second marriage was a miracle too. What a life I had with him and now the memories.”

Amen!

Finally, David recalled that “after graduation we Evans alums became occupied with our professions, families, and communities, but worked at staying in touch as best we could. As we approached retirement age, a group of us began annual on-campus weekend reunions of golf, Wolverine football, Harv’s beloved Michigan marching band, and general camaraderie.

When the annual reunions were temporarily interrupted by COVID, Harv suggested that we try an occasional one hour Zoom meeting.” That was more than four years ago. The Zoom meetings soon began taking place weekly, and we rarely miss a scheduled meeting. Harv’s sudden death shocked all of us; and suffice to say that it has left a hole in our collective hearts. However, we have soldiered on with our weekly meetings without him. I send you this message because, based on your touching tribute, I suspect that you can understand how, and why, we miss him so dearly.”

You said it brother (to the brother(s) I never knew I had).

Fast forward to today. A bunch of East Texas band kids from the 1970s and 80s who were willed into becoming a legendary college band by Jim Keene, took their own turn at paying forward the debt they owed him by creating an endowed scholarship and naming the Band Hall in his honor at the newly rechristened East Texas A&M University (the place where he was quite possibly the happiest). Now a few more music students in East Texas will be able to pursue their musical goals thanks to Mr. Keene—a person they will never meet. That’s what I call paying it forward. Note: the caddies also pitched in on the scholarship.

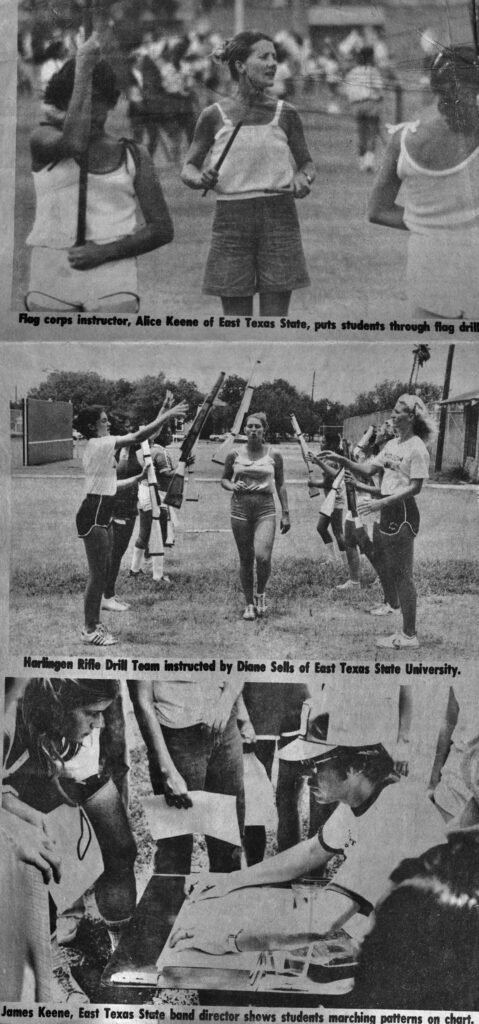

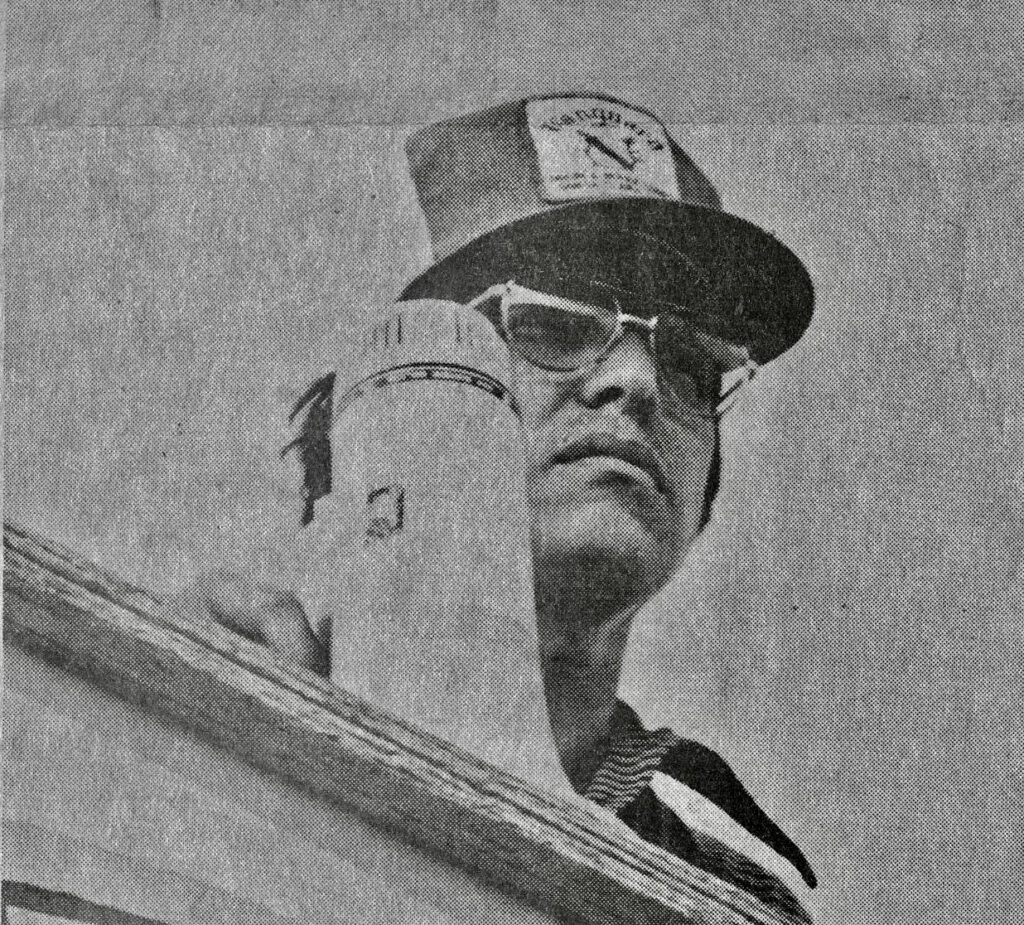

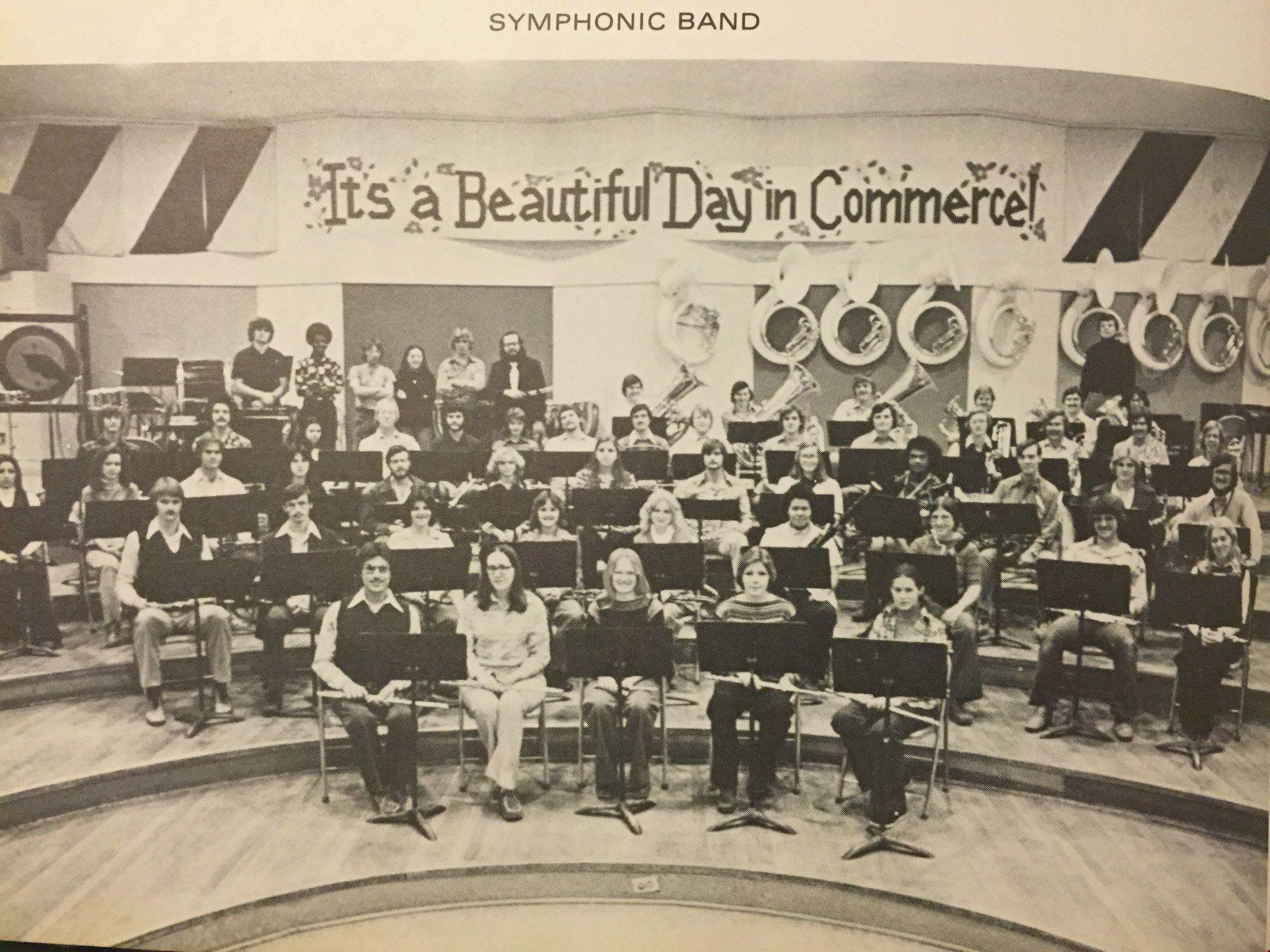

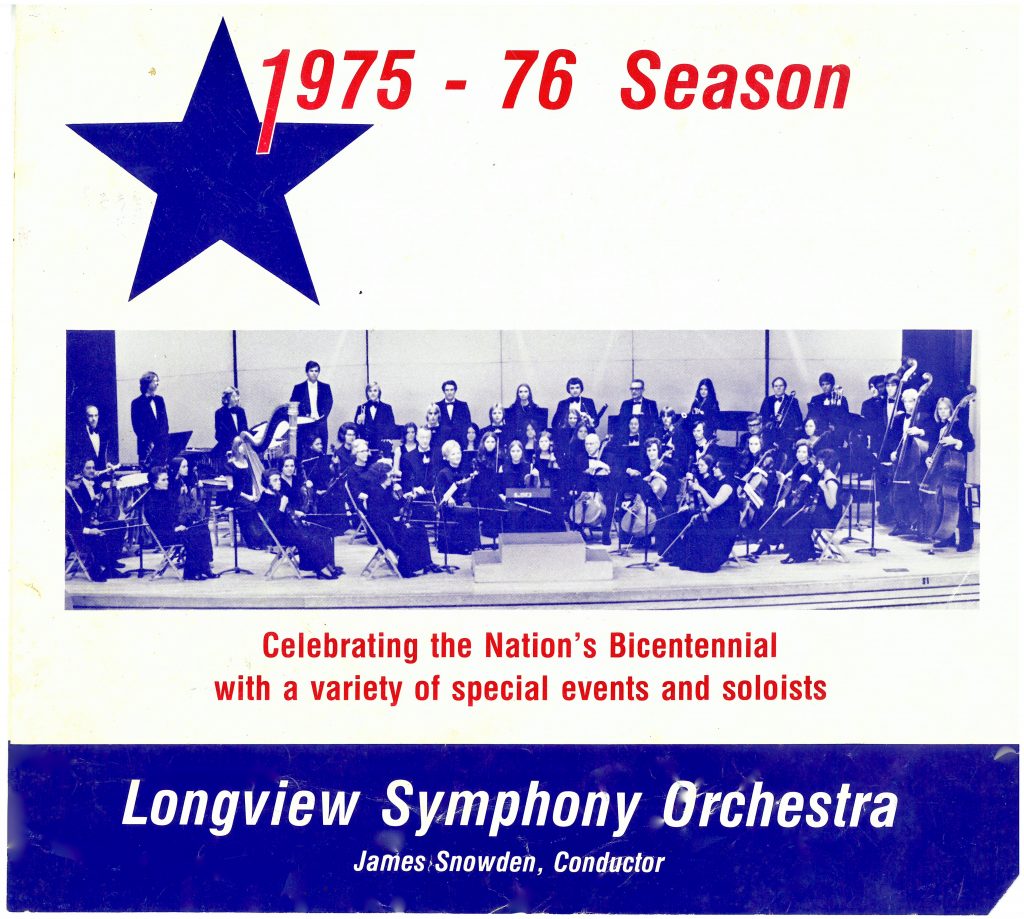

Why would I say that the East Texas Band was legendary? Well, in just a few short years Mr. Keene turned the little-known East Texas State University Music Department into a hotbed of band performance that thrust the school into the spotlight of Texas Band programs. He became the catalyst that allowed the quiet excellence of the ET faculty to shine through the pine curtain of East Texas. Then, a memorable performance at the Texas Music Educators Association Convention turned heads and launched the department as a destination for some of Texas’s most successful band directors, educators, and performers. Later that spring the ETSU Trombone Choir, under the direction of Dr. Neill Humfeld would be featured at the National Trombone Workshop in Nashville, Tennessee. ET was on fire in 1979!

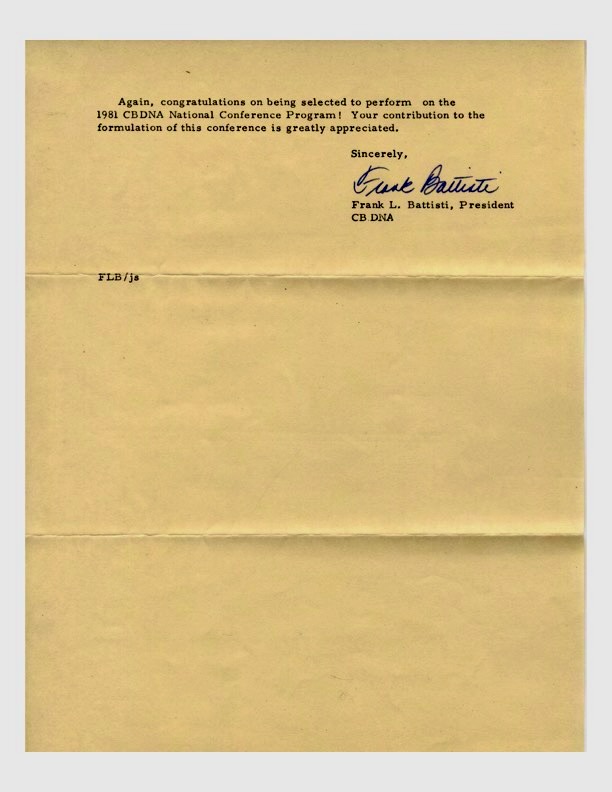

Additional proof of the band’s legendary status was kept secret for more than 40 years. In 1980 the ET Band received an invitation to perform at the prestigious College Band Directors National Association (CBDNA) Convention which would’ve advanced the school’s reputation even further.

Unfortunately, at the time the invitation was received, Mr. Keene had accepted a position as Director of Bands at the University of Arizona. This, of course, meant that without the director who led the band at the time of the application, the invitation was withdrawn.

Keene told me he was leaving ET as we sat together on the bottom of a bunkbed at the Lone Star Steel Band Camp where we were teaching together in June of that year. I remember he put his hand on my shoulder as I cried when he told me he was leaving ET. It was my first lesson in the cruel subtleties of the collegiate job market that I would come to navigate myself in just a few short years.

Later that summer Keene and I dropped a pregnant Alice off at the Dallas Fort Worth airport and he and I drove their two cars in caravan from Texas to Arizona. After arriving in Tucson, we then trekked across the desert to LA to see the Odyssey Classic Drum Corps Show while Alice unpacked boxes in their new home. It was a two-six pack trip that was fun, galvanizing, and the best—worst—summer of my young life. We were going to miss him dearly at Old ET and I knew it.

No one—not even his closest friends—knew of the invitation to perform at CBDNA until the letter was discovered among Keene’s papers at the University of Illinois. To my knowledge he never told anyone. What a tremendous honor it would’ve been for Keene to make a triumphant return with his ETSU Band to perform at CBDNA on the campus of his alma mater the University of Michigan.

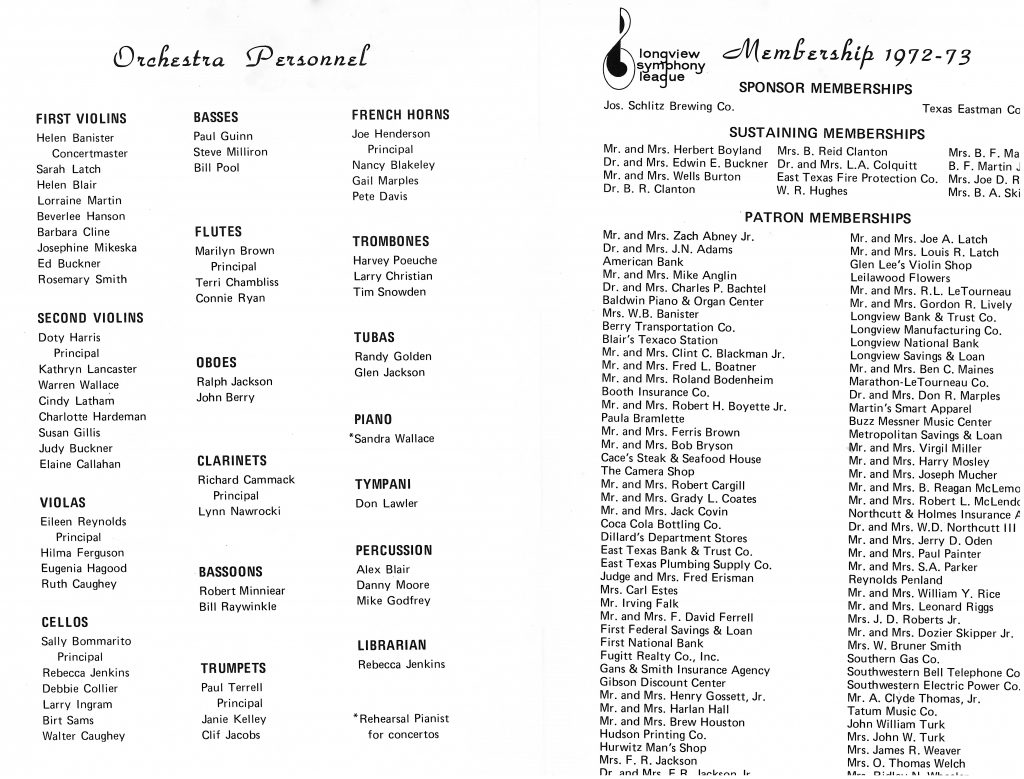

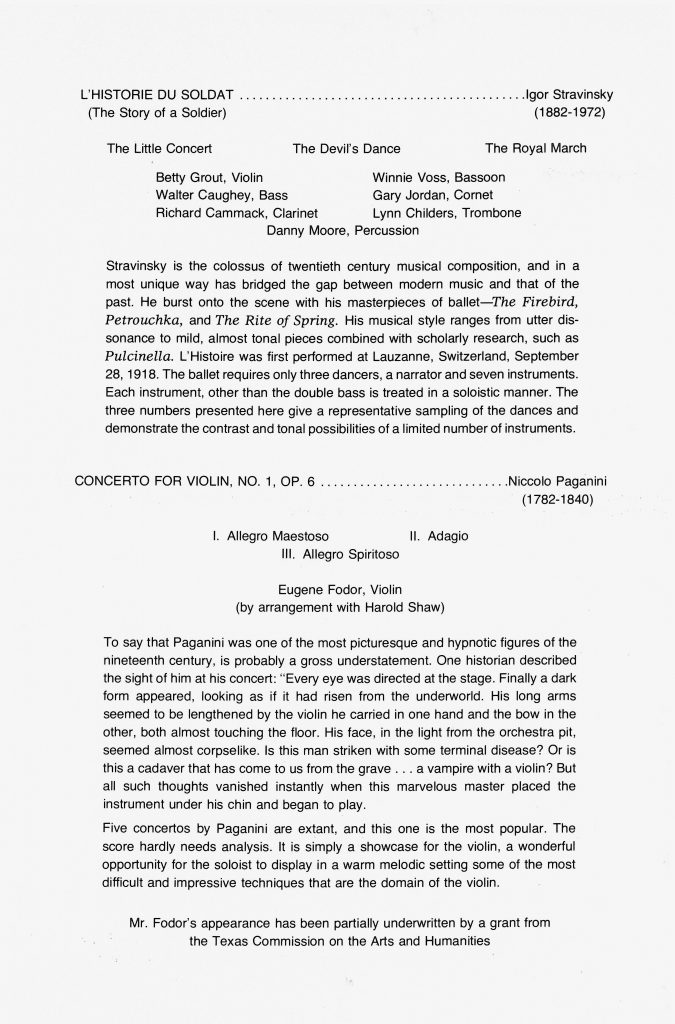

In retrospect, Mr. Keene had likely been working toward this achievement throughout his tenure at ET. Over the years he had invited several influential Band Conductors to Commerce to work with our band including Mark Hindsley (who Keene would eventually succeed as director of bands at Illinois), Col. Arnold Gabriel (U.S. Air Force Band), composer Karel Husa, and the founder of CBDNA (and his college mentor), William D. Revelli.

Revelli’s visit was a remarkable experience as we had heard so many stories about him. We knew we had prepared well for this concert, but the band was so on edge in preparation for the maestro’s visit that the air was thick with tension the day Revelli arrived in Commerce, TX.

I remember sitting on stage as our band nervously warmed up when Mr. Keene and Maestro Revelli suddenly appeared at the back of the auditorium. Instantly the band fell silent; everyone stopped playing and the two walked in reverent silence to the front of the stage. Mr. Keene made a superfluous introduction of Revelli, but no one heard it or remembers it. We knew who he was—legend in his own time, blah, blah, blah—and we were ready to play. I don’t think we even warmed up or tuned which was always a 15 to 20-minute ritual of any Keene rehearsal. But we had no way of knowing what would happen next.

I will never forget how Revelli stepped to the podium, called for us to play Festive Overture, raised his baton, and conducted the Shostakovich from beginning to end without a stop. When we had finished, he placed his baton on the music stand, turned to Keene and said “Jim, what is there to rehearse? It is perfect.” Again, we sat in stunned silence, not knowing what to think about what had just happened. Keene too was uncharacteristically speechless and simply suggested that he move on to the Persichetti.

Legendary!

Of course, when it came to the Vincent Persichetti Symphony for Band Op. 96, Revelli had plenty to say. I remember quite clearly him taking the principal oboist to task over a phrasing he wanted to hear before turning his attention to a certain percussionist whom he attacked (with a vengeance that Mr. Keene could only dream of), and whose name shall remain anonymous. The legends about Revelli were all true and we watched them unfold in real time.

The concert the following evening was no less inspiring and I’m sure that a good word was put in to then president of CBDNA, Frank Battisti of the New England Conservatory, upon Revelli’s return home.

In case you are a musician who knew Mr. Keene, or were ever in one of his bands, you might want to know why he was particularly hard on clarinetists. After all, sax was his primary instrument, right? The photo below might help shed some light on that question. Note the clarinetist sitting on the outside of the last row to the left of the renowned Michigan Symphony Band. I’ll give you a minute…

But how could a person who was such a stern taskmaster as Jim Keene have so many friends to count at the end of his life? Perhaps because, as his friend and college classmate David Devendorf would say, now you have “a better understanding of the source of the character that our Harv was, and the strength of character that he possessed.”

Perhaps Charles Spurgeon said it best: “A good character is the best tombstone. Those who loved you and were helped by you will remember you when forget-me-nots have withered. Carve your name on hearts, not on marble.”

Tonight, the name James F. Keene is indelibly carved on my heart, and “I suspicion”—as Keene would say—on that of many others as well.

A Parting Shot:

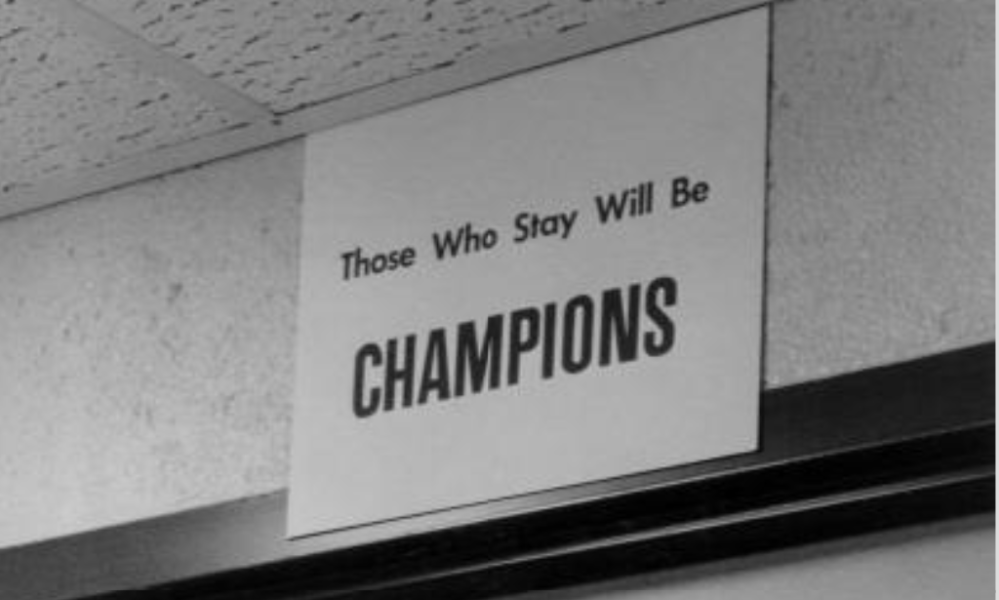

Keene always referred to his college classmates at Michigan as “Doctors, Lawyers and Captains of Industry.” His college roommate David Devendorf recalled that “we all arrived on the U of M campus only a year before our legendary football coach, Bo Schembechler. When Bo was hired, many characterized the culture of Bo’s predecessor (Bump Elliott) as a ‘country club.’ Bo knew that he would need to deal with the attrition that would occur when he carried out his own plan to convert the ‘country club’ atmosphere into a ‘boot camp.’”

It bears noting that the first person to walk into Coach Schembechler’s office upon his arrival at Michigan was none other than Michigan Director of Bands William D. Revelli which sparked a friendship between the two as they both shared a common work ethic and approach to running their respective organizations.

Bo managed the task of reforming the team in part by challenging them with a sign that he hung in the locker room that read: “THOSE WHO STAY WILL BE CHAMPIONS.” David recalled that “a week or so into spring practice a small group of seniors had seen and experienced enough of the program Bo was building. On their way out of the locker room door for the last time, they hung their own sign adjacent to Bo’s. The departing seniors’ sign read: ‘AND THOSE WHO LEAVE WILL BECOME DOCTORS, LAWYERS AND CAPTAINS OF INDUSTRY.’”

“Like the rest of us caddies, our Harv loved the players who stayed and became champions (UM 24-OSU 12 in 1969, Bo’s first game against Woody). …but Harv also admired those departing seniors who had the courage to vote with their feet, and to do so with style. Our Harv mentioned those guys, over the years, fondly and frequently.”

After a bit of online research, it appears the actual quote was scrawled on the bottom of the original sign with a black marker that read …”and those who leave will be doctors, lawyers, bishops, generals, captains of industry, and heads of state.” But I think you get the picture.

A new printed sign soon replaced the graffitied one in the Michigan locker room.

Citations:

Those Who Stay: The Saving of Michigan Football (Episode Six)

U-M Bentley Historical Library

Thanks to David C. Devendorf for his “Keene” insight. (lightly edited)

Thanks to Bruce Richardson for his work in researching Mr. Keene’s papers from the archives of the University of Illinois Champaign—Urbana

Photos courtesy of Alice Keene, Dan & Liesa Moore, and the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library