Art as Transaction

In a previous post, I wrote about the importance of repetition (meaning: practice) in the creation of art. I talked about Vincent Van Gogh and his love of painting sunflowers. One of his most famous paintings is a still life titled Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers of which he created as many as twelve different versions (a large portion of the world today only knows about the one that appears on posters, tote bags, and coffee mugs). Van Gogh painted sunflowers over and over again to gain mastery of color. He wrote to a friend that they were “painted with the three chrome yellows, yellow ochre and Veronese green and nothing else.”

Practice is certainly important but that is not the end of the story. Great art also requires passion, desire, originality, and commitment. Some people might see the Life Artistic as a lazy get-rich-quick scheme, or as Mark Knopfler ironically put it, “money for nothing and your chicks for free.” But once you look deeper you begin to understand that creating art is a lifelong pursuit with no guarantees of success. Thankfully, this fact does little to discourage talented artists from the chase.

Musicians such as the renowned cellist Pablo Casals or drummer Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones lived their entire lives with the goal of making steady improvement over time. Why? Because they were compelled to do so. It was the journey more than the outcome that motivated them to pick up the cello or the drumsticks every day and put in work.

Guitarist Eddie Van Halen once said that “a lot of people want to be successful so they can go out and party and have fun. But for me, making music IS the fun part.” To Charlie Watts, “success meant being good enough that you would get to play every night.” These musicians clearly made a lot of money playing music yet their passion doesn’t seem to be motivated entirely by financial gain.

Perhaps one of the most popular stories about achieving musical proficiency is that of Robert Johnson who, as legend held, sold his soul to the devil in return for becoming a great blues player. Guitarist and self-proclaimed musical minister Rory Block says “I never understood the idea that blues was the music of the devil. I think anything that has incredibly deep emotion and resonates with people in a life-changing way is of a spiritual nature.”

Those who knew him would say that Johnson was not a particularly good blues musician when he first started playing in public. What seems to be missing from the story is the fact that Johnson took two or three years off from performing to study with other musicians and to practice. He returned as a much-improved musician which led one of his former teachers, Son House, to make the off-hand remark that “he must have sold his soul to the devil to be able to do that.” And with that a legend was born, or at least a pretty good movie. But in reality, there was no deal with the devil, no mystery, just good old-fashioned purposeful practice (steady improvement over time).

“What seems to be missing from the story is the fact that Johnson took two or three years off from performing to study with other musicians and to practice.”

In my opinion, far too often people see music making as transactional. It is the idea that if I practice and get good, fame and fortune must surely follow as long as I play the music that has already been proven successful by someone else. This type of transaction is commonly focused on achieving financial gain or a career objective, rather than on a genuine desire to create originative works of art that stand on their own merit. Dick Schory, the creator of the Percussion Pops Orchestra of the 1960s puts it like this. “The entertainment business is a business of copycats. If something is successful, then everyone thinks that they can be successful, too, by copying it.”

To me, real music making is a lifelong pursuit. It is more marathon than sprint, more failure than success, and more outcome than income. Having the passion to create is just as important as putting in the hours of repetition necessary to build technique. Writer and director, Nicholas Meyer, says that “you can’t teach talent, but you can teach technique.” Sometimes however, lightning will strike when technique combines with desire, is fueled by talent, and graced with a little bit of luck, but there is certainly no implicit guarantee of a successful transaction. Renowned drummer Billy Cobham once said, “there are gifts but it may be the gift on an idea.”

“…real music making is a lifelong pursuit. It is more marathon than sprint, more failure than success, and more outcome than income.”

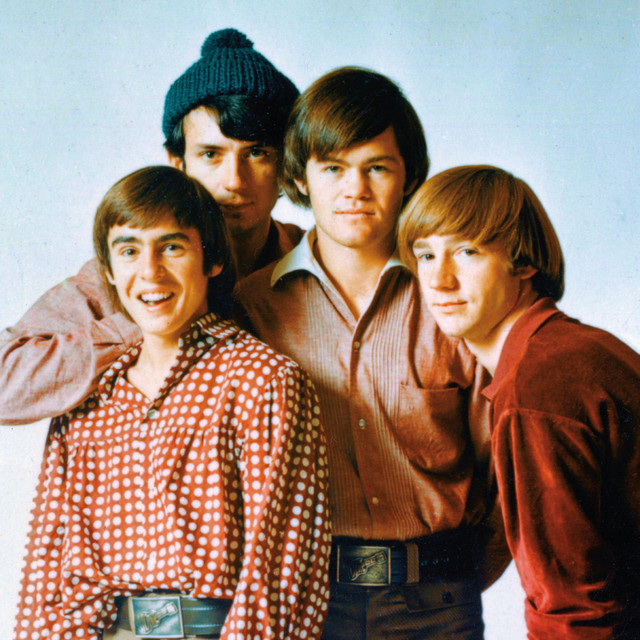

There is perhaps no better example of this phenomenon than in the story of the Monkees. Theirs is a classic tale of transactional music making yet with a somehow satisfying twist.

If you don’t know about the Monkees, you are either under age 50 or not interested in American pop culture from the 1960s. An oversimplified summary of their story is to say that the Monkees were a manufactured product created for a comedy television show based loosely on The Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night. They were to be the American answer to the Fab Four. Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith, Peter Tork, and Micky Dolenz were chosen from over 400 applicants through purely acting auditions and unconventional job interviews. There was only a passing concern about their ability to play an instrument or sing.

Once assembled, the Monkees had a rather inauspicious start to their collective (music) career. Mike Nesmith and Peter Tork had previous experience as working musicians; Nesmith and Jones had already made a few recordings prior to the Monkees and Davy had done song and dance work as well as some musical theater, most famously in the play Oliver. Micky Dolenz was a child-actor who fronted his own rock band called “Micky and the One-Nighters.” He possessed a classic rock and roll voice but had little to no experience as a drummer—his assigned instrument for the show.

Responsibility for the music came to record producer Don Kirshner who worked with a group of legendary studio musicians known as The Wrecking Crew. That group included seasoned studio musicians such as Glen Campbell, Leon Russell, Tommy Tedesco, Julius Wechter, Carol Kaye, Hal Blaine, and others. For the first Monkees single, Last Train to Clarksville, Kirshner turned to the song writing team of Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart.

The Wrecking Crew recorded the instrumental tracks while only one member of the Monkees actually appeared on Last Train to Clarksville—Micky Dolenz—who sang lead. It was their first single and it became a hit almost as soon as it was released in 1968 just a short time after the show began airing. The music team quickly followed up with another hit, I’m a Believer, also sung by Dolenz, and everything seemed to be going to plan.

There is much debate as to what drove the success of the Monkees. Was it the music that got people to watch the show or was it the show that sent people to the record store? Either way, it was working, but there was trouble in paradise. The individual Monkees were unhappy that they weren’t allowed to contribute more to the creation of their music. Kirshner fought their involvement because he felt they had a good thing going with the studio musicians, and he didn’t want to change the formula.

But in the minds of Mike, Peter, Davy, and Micky, they felt uncomfortable being successful “recording artists” without playing on their own records. In the film The Wrecking Crew Dolenz explained: “I think there was a lot of resentment in the recording industry that we’d come out of nowhere, left field, and sort of just shot right to the top without having to kind of go through the ropes.” They felt humiliated that they were a band with hit records yet didn’t actually help create or even play the music.

This conflict and other issues related to the television production continued to grow and eventually led to the cancellation of the show after the second season. When their feature film, Head, became a box office flop, it looked as though the Monkees were finished. One scene in Head perfectly epitomized their frustration with their reputation as a band that didn’t create or play any of their own hit music.

Frank Zappa, an unlikely champion for the group, befriended the Monkees and appeared on both their television show and in the film. Zappa enjoyed their irreverence if not their musical ability. In the film, Head, Davy Jones performs a polished Hollywood style song and dance production number written by Harry Nilsson and choreographed by Tony Basil. Davy wears a classic tuxedo and tails that switches dizzyingly between all black and all white throughout the montage.

After finishing the possibly photosensitive seizure inducing number, Davy and a group of somnolent teenagers emerge from a sound stage onto a studio back lot alongside a large bull being led by Zappa (metaphors abound). Jones asks “what did you think?” to which Zappa replies “the song was pretty white.” Jones says with a smile, “so am I, what can I tell ya?”

Zappa’s delivery is more droll than ironic at this point and he continues, “You’ve been working on your dancing, though it doesn’t leave much time for your music. You should keep working on your music. You should spend more time on it because the youth of America depends on you to show the way.” Davy responds with a cheerful and optimistic “Yeah?” as if he’d just been given a compliment. Then Zappa’s voice shifts to sarcasm as he responds, “Yeah.” He leads the bull away with only the doleful sound of the bell around the bull’s neck. Davy then breaks the fourth wall looking into the camera with a bemused expression.

But the Monkees were determined to prove that they could indeed play and sing by releasing their own albums and touring in various incarnations for many years. Dolenz said in interviews that “it’s like Leonard Nimoy really becoming a Vulcan, we became this band.” Although Peter Tork, Davy Jones, and Michael Nesmith have now passed away, Dolenz continues performing and touring in tribute to his bandmates.

Here’s the twist: the Monkees continued to develop their craft both collectively and as individuals for the rest of their lives. They continued practicing and working at their art in pursuit of excellence. Before his passing, Mike Nesmith and Micky Dolenz doggedly continued to hone their skills as musicians, song writers, and recording artists. Their last project together is called Dolenz Sings Nesmith, on which Dolenz and company created new arrangements for songs penned by Nesmith. It is an enjoyable album that shows how far Dolenz has come as a musician and record producer and how good Nesmith really was as a songwriter.

Neither gave up their pursuit of music, or the desire to make daily progress. They just kept painting sunflowers. And so should you….

Citations:

Contributors, “Sunflowers,” Vangoghmuseum.ni. https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0031V1962

“Nothing but Sunflowers in a yellow earthenware pot. Painted with the three chrome yellows, yellow ochre and Veronese green and nothing else,” Vincent van Gogh to Arnold Koning, on or about 22 January 1889.

Moore, Daniel Preston, The Impact of Richard L. “Dick” Schory on the Development of the Contemporary Percussion Ensemble, Dissertation, UMI, 2000

Hey, Hey We’re the Monkees, TV Movie documentary, Alan Boyd, director, Chuck Harter, writer, 1997

The Wrecking Crew!, Documentary, Denny Tedesco, director, 2008

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1185418/

A Parting Shot:

Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart wrote the upbeat and happy sounding Last Train To Clarksville as a protest to the Vietnam War. There is a certain lyrical dissonance as the driving guitar riff is contrasted with lyrics about being drafted and shipped off to war. The train is taking the protagonist somewhere to a military base and he knows that he may die in the war. “I don’t know if I’m ever coming home” is a poignant line set against the upbeat backdrop of the song. In keeping with the spirit of the obvious comparison of the Monkees to the Beatles, Hart wrote the prominent Oh No-No-No, Oh No-No-No” lyrics as a response to the Beatles famous “Yeah Yeah Yeah.”

Here’s a cultural collision. An American percussion group performing an avant-garde influenced version of Last Train To Clarksville, in Argentina! I think the Monkees would’ve loved it.