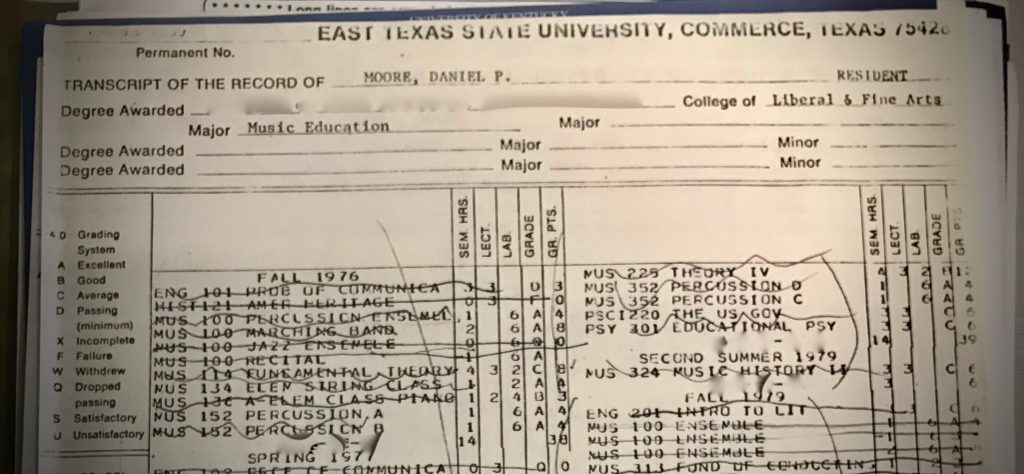

My three-year association with the Sky Ryders Drum & Bugle Corps from Hutchinson, Kansas, was a memorable time. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, competitive drum & bugle corps was just beginning to be a thing in Texas. Fortuitously, I matriculated to East Texas State University, where our band, under the direction of James F. Keene, was among the first Texas college bands to fully embrace the Corps Style.

Jim Keene had become somewhat of a guru to the drum corps activity. Corps like Blue Stars, Bridgemen, and Phantom Regiment would find their way to Commerce, TX each summer to rehearse and maybe do a clinic or an exhibition performance but primarily to be advised by Keene. Because of Mr. Keene’s influence, ET students began participating in DCI: some classmates went west to Blue Devils and Santa Clara Vanguard, and a few went north to Kansas and the Hutchinson Sky Ryders. My friend Bruce Richardson marched in 1980 and then wangled himself an unpaid position on the brass staff in 1981, and managed to get me one of those sweet unpaid gigs as a snare tech. That year we contributed an arrangement of Lyle Mays’ Overture to the Royal Mongolian Suma Foosball Festival. It got cut mid-season.

Corps director George Tuthill and brass instructor John Simpson were both fully pedigreed in the drum corps activity and shared a singular goal: Get the Sky Ryders into the DCI top twelve. This was a task the Sky Ryders had yet to accomplish and the pressure was on to get the job done. Tuthill and Simpson were either in each other’s pockets or at each other’s throat depending on the day.

George welcomed me into the spartan apartment he shared with his two young sons and two incorrigible basset hounds. At night I had to compete with them for sleeping space on the couch (the dogs, not the boys). George and I spent hours at his kitchen table discussing percussion arranging, drum corps history, jazz, and many other topics. He mentored me in the old school manner. He was tough and opinionated and we often disagreed on arranging for percussion, but George was ahead of his time in drum corps. His percussion features were more like contemporary percussion ensemble pieces, precursors of percussion features that would become the norm by the 1990s.

On the other side of the street, I was hearing from John Simpson what he expected from a percussion arranger. John was known for his expertise in bringing out the best in brass players through his work with the Bayonne Bridgemen.

The Bridgemen boasted one of the top drumlines in the nation, under the leadership of Dennis DeLucia. Simpson felt the drumline’s success was sometimes to the detriment of the hornline. In one show, the corps was spread out across the field, and the horns needed to make a syncopated attack that they could never get. Simpson asked DeLucia about adding a fill before the hit, but it never materialized. Finally, John whispered in the ear of the #5 bass drummer and asked him to play a single note as a setup for the horns. The bass drummer complied and the problem was solved. As a spectator at the time, I thought it was an understated and hip moment, and it was courtesy of the horn guy.

My interactions with George and John were often heated and volatile, causing many to think we didn’t get along. Yet at the end of the day, I always felt welcome in George’s home for another round of noisy discussions and to battle the dogs for supremacy on the couch, and John would go out of his way to defend me to judges or corps members grumbling about our scores. We were all passionate about our work and improving the corps.

In those days, drumline scores weren’t linked to the other captions. It was possible for a drumline to win high drums while the hornline languished at the bottom of their caption. The Bridgemen were enjoying a three-year run as the top drumline while their corps finished overall in the middle of the pack (except in 1980 when they finished 3rd in finals). Judging criteria was changing in DCI, but at the time, these were the facts of life: the best snare line and best soprano line wins.

When I took over as Sky Ryders percussion arranger/caption head in 1982, I knew we had to do two things: 1) Develop an offseason program and 2) help the hornline maintain their upward trajectory. To that end, I recruited players from the Dallas/Fort Worth area and began holding winter camps in Commerce. The Kansas guys came down and we made great progress.

In writing the book, everything I composed was designed to make the horns sound great. We knew we weren’t going to win a drum trophy that year, but we might not be on a bus heading home on finals night like we were in 1981.

We made incredible strides as a corps in 1982. We were sounding good and looking good and all eyes were on our rifle line. The rifles were at the top of the “what to watch” list in our show. Drum Corps World called it the “Show within the Show.” The hornline was hotter than ever, and kept getting better throughout the season. The drumline improved dramatically as well but continued to be outscored by drumlines of corps who were nowhere near our level. It was frustrating winning shows while coming in fourth or fifth in drums, but I knew that support of the hornline was more important to our collective success.

The drumline was being held back by our low “Exposure to Error” (the difficulty of the music) and “General Effect” (overall effectiveness of the music) scores, but there were more points available in the “Execution” (how cleanly the music is played) column so we focused our energy there. We edited parts and kept cleaning all season. Those inside the activity recognized what we were doing and acknowledged it long before the judges did.

At Drums Along the Rockies in Denver — the biggest show we had been in all season — the drumline wanted to make a respectable showing against lines that had been killing us all season. Tension was high. The line was extremely nervous and the only place we could find to warmup was on a busy corner near Mile High Stadium.

We finished our first warmup and it wasn’t good. I was about to launch into a lecture about the need to get focused when we heard a loud “Hhhhheeeeeeeey!” and the roar of a Harley. The line tried to maintain focus, but their eyes were clearly tracking something. I turned around to behold a motorcycle gliding by with a young woman on the back, shirt pulled up over her head, leaving nothing to the imagination. We stood, dumbfounded, then everyone burst out laughing uncontrollably. We pulled it together, played a few more notes, then headed to the gate. The tension was broken. Everyone was loose, relaxed, and extremely focused going onto the field.

That night the line transcended. They granted drum major Milt Allen’s request to “leave it all on the field.” We beat everyone in execution except our arch rivals, the Freelancers (who bested us by one-tenth of a point). Although we finished fifth in drums, it was a huge victory for us and it inspired the line to dig in and really start cleaning.

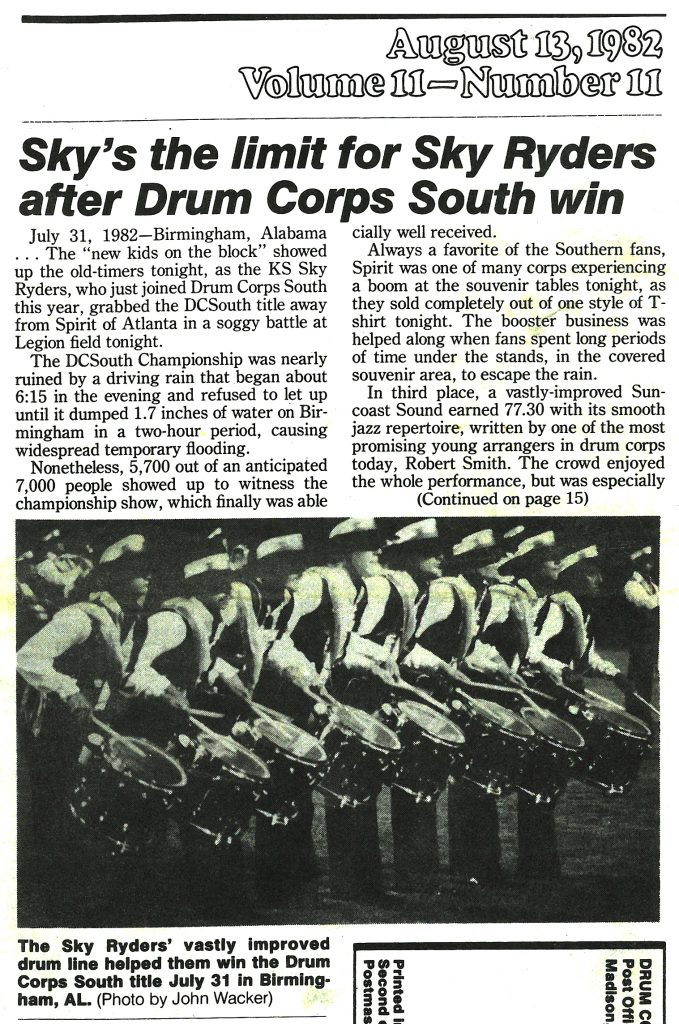

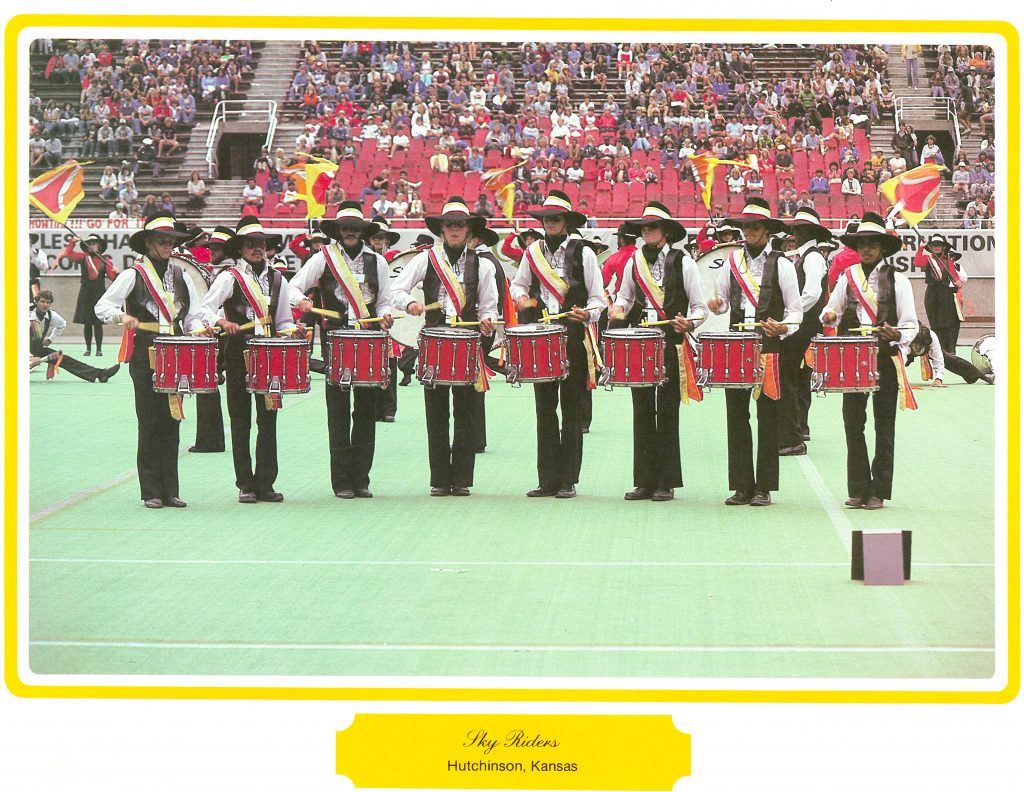

By the time we made it to the finals of Drum Corps South, we were beginning to receive some credit for our support of the brass section. We placed second in drums to Spirit of Atlanta, losing by only two-tenths of a point. This time we won in exposure to error and general effect but lost in execution (possibly as a result of our after-midnight start time due to a stressful two-hour rain delay). The judges were beginning to appreciate that our book was designed to groove rather than just be a gratuitous display of chops. My happiest moment that season came when Drum Corps World posted a front-page photo of the Sky Ryders drumline with the caption “The Sky Ryders’ vastly improved drumline helped them win the Drum Corps South title July 31 in Birmingham, AL.”

That season the corps didn’t need us to be great: they just needed us to be good. And that’s what we were. We provided a solid foundation that propelled us into finals and gave us something to build on for the following season. A photo of the drumline — not the hornline and not the rifles — represented the Sky Ryders in the official DCI Calendar for the following year. Pretty Cool.

By the time we reached prelims, many of the top percussion caption heads such as Marty Hurley, Ralph Hardimon, Tom Float, Dennis DeLucia, and Fred Sanford took me under their wings, and each of them (in their own way) told me that we had what it takes to make finals for the first time in Sky Ryder history. We finished the season in 10th place overall and 12th place in drums.

This year, the bus ride home would have to wait until after finals, thanks to a good drumline.