As if 2020 couldn’t get any worse, in its final hours it claimed Mary Ann. Known to the world by that name, the actor Dawn Wells (82) died on December 30, reportedly of COVID-19 related complications. She played the smart, wholesome, eternally optimistic Mary Ann Summers on the enduring sitcom Gilligan’s Island from 1964 to 1967. The show ran only three seasons and was well into reruns by the time I took notice of it or Mary Ann, but in those 98 episodes both she and the show had secured their place in television history.

The show also launched the long-running debate, “Ginger or Mary Ann?” Essentially, which character has the qualities you prefer: the down-to earth, cute Mary Ann, or the high-maintenance, glamorous Ginger? From CBS to USA Today, there have been countless polls to settle the question; there is even a Facebook page which assures us that this is an important subject. Spoiler alert: Mary Ann remains ahead of Ginger by about 3 to 1. In a 2001 interview, Bob Denver (Gilligan) said that Mary Ann would typically receive 3,000–5,000 fan letters weekly while Ginger might get 1,500 to 2,000.

Dawn remained close to her Gilligan’s Island costars, particularly Russell Johnson (The Professor) and Bob Denver (Gilligan). The trio appeared together for countless fan events and “Three-Hour Tours.” While some actors try to distance themselves from their TV characters, Ms. Wells embraced her iconic status.

In the forward of her book, What Would Mary Ann Do? A Guide to Life, Russell Johnson wrote: “We love Mary Ann because she is the future, the hope of our world. The youngest of the castaways, Mary Ann has her entire life in front of her. Watching her unfailing good cheer, her optimism is never in question. We love her because we need her emotional support and her belief that all will turn out well.…We love Mary Ann because of Dawn Wells.”

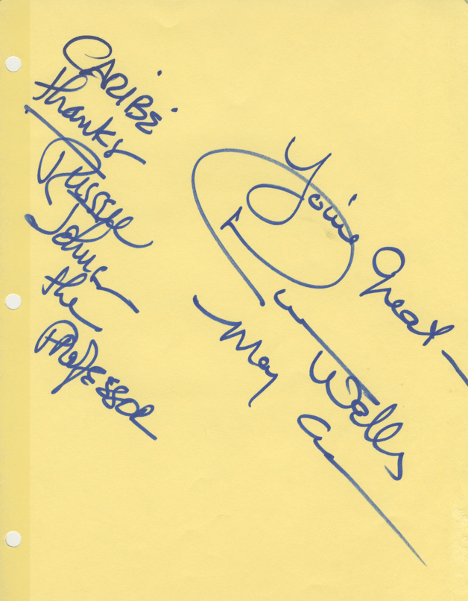

In 1995, I got to play a Three-Hour Tour gig on a Cincinnati barge decorated to look like a Tiki boat and renamed the S.S. Minnow. In a scene no doubt reenacted countless times throughout their careers, Bob Denver, Russell Johnson, and Dawn Wells were welcomed aboard to the Gilligan’s Island theme song and enthusiastic applause. The passengers enjoyed a dinner cruise on the Ohio River and questions/answers with the trio of stars, followed by a meet-and-greet and autographs.

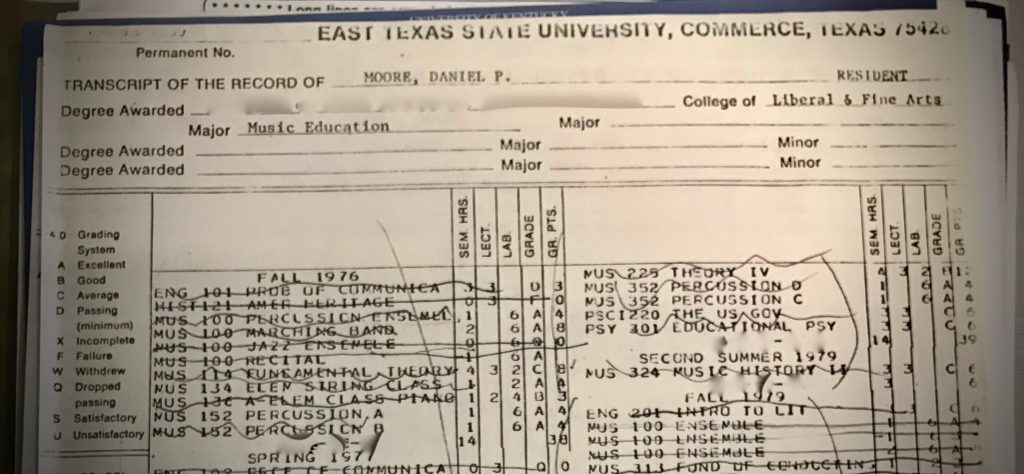

Our band was called Caribé and featured steel pan players Mat Britain and Dave Barr, bassist Michael Sharfe, and yours truly on marimba and drums. We provided background music from our position directly behind the stars.

I was closest to Bob Denver. At one point I leaned over and whispered, “Forget this Gilligan stuff, what would Maynard G. Krebs want to hear?” Denver had played the jazz-loving, beatnik sidekick Krebs on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, the role that preceded his run as Gilligan. With a sidelong glance over his shoulder, he grinned, “Probably anything by Monk.” The band called up Straight No Chaser by Thelonious Monk and he instantly burst into laughter, amazed that our Caribbean-styled band could produce Monk on steel pans and marimba.

At the first opportunity during the cruise, Gilligan and then the Professor disappeared. But not Mary Ann. She stayed and listened intently to every person’s story, demurred at their proposals of marriage, and blushed at their compliments on her beauty (at 57, she still had the beauty that got her the role as Mary Ann in the first place, beating out none other than Raquel Welch for the part).

At one point, she bade the band to stop playing so a fan could sing to her the Gilligan’s Island theme in its entirety — word for word and with choreography. As she listened, she smiled without a hint of embarrassment or mockery. Sure, Dawn Wells was an actor and might have been playing a part, but she was so sincere and non-judgmental that it was moving to watch. She was a beautiful person.

At the end of the night, the crowd was ushered off the boat and the band waited around for Bob and Russell to reappear. As the audience departed, a few people asked where Gilligan had gotten off to. Completely in character, Dawn improvised a clever line that he had been piloting the boat all this time. As the stars gathered themselves to depart, the band gathered around Dawn and declared to her that we had decided the question once and for all — it’s Mary Ann. She smiled that Mary Ann smile and blew us a coquettish kiss before skipping down the gang plank and disappearing into her waiting limo.

I think Dawn said it best in her book: “I learned that the belle of the ball doesn’t have to be a belle. I learned that beauty is an illusion. You make the very best of what you have, what you are, and what you can be. I still believe that.”

Bon Voyage, Mary Ann.

Dawn Wells (1938-2020)