It’s no secret that I struggled academically throughout high school and into college. By eighth grade, I was so single-minded in my desire to be a musician (or a drummer anyway) that I focused all my energy in the band hall and didn’t pay much attention to the whole “school thing.”

For the greater part of my young life, the people who most influenced me were music teachers—band, orchestra, and choir directors—so it seemed only natural that I follow in their footsteps. Being a band director, however, required going to college which was something I never gave much thought until halfway through senior year. It was also a feat that I had no clue about how to accomplish.

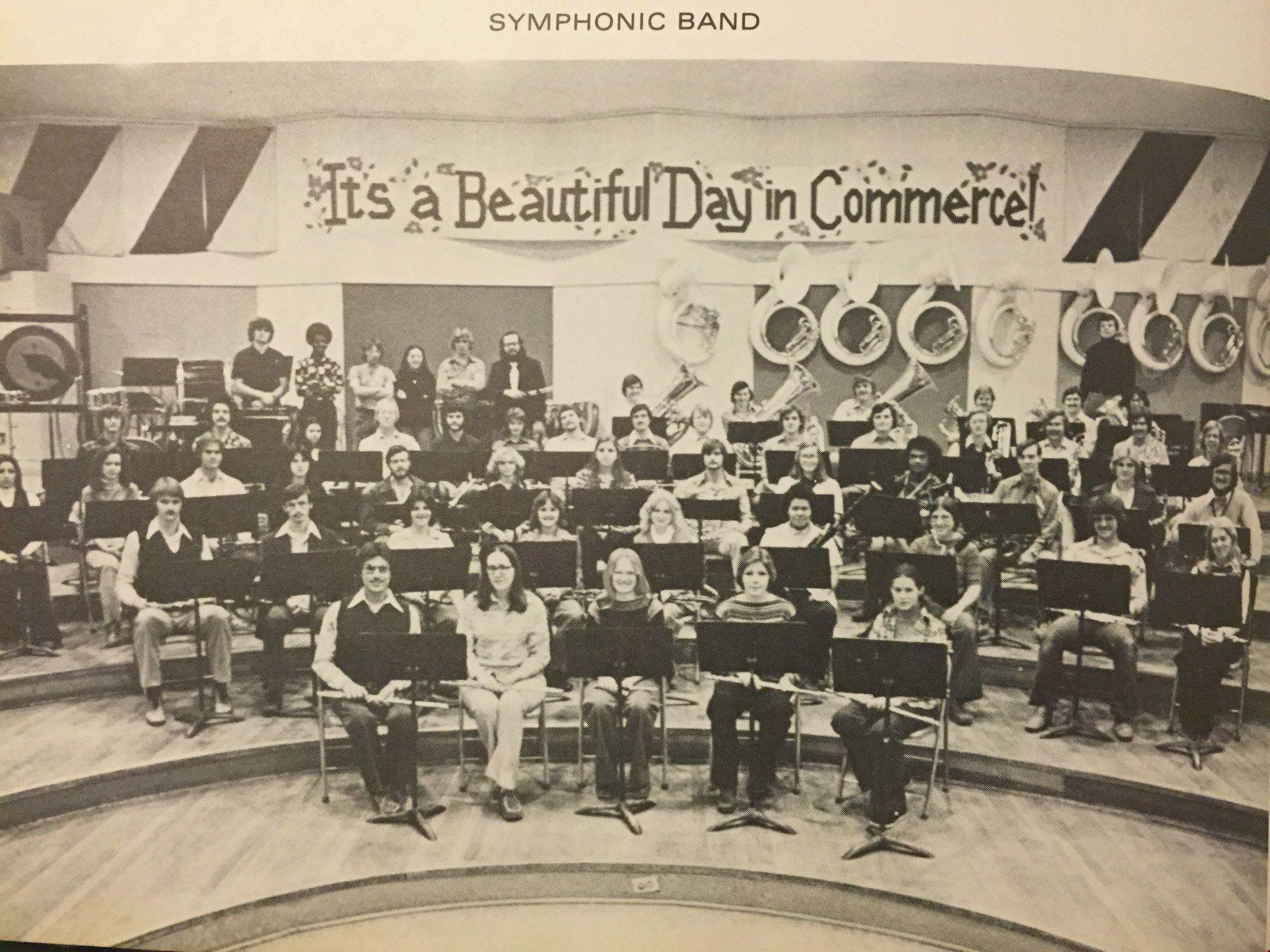

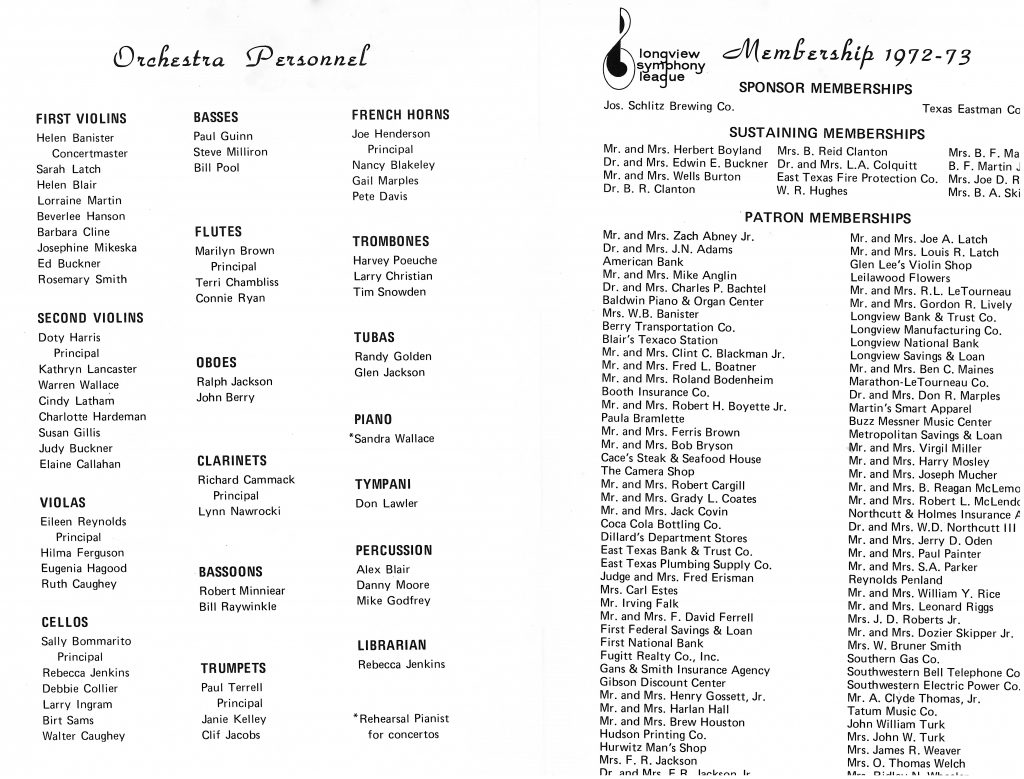

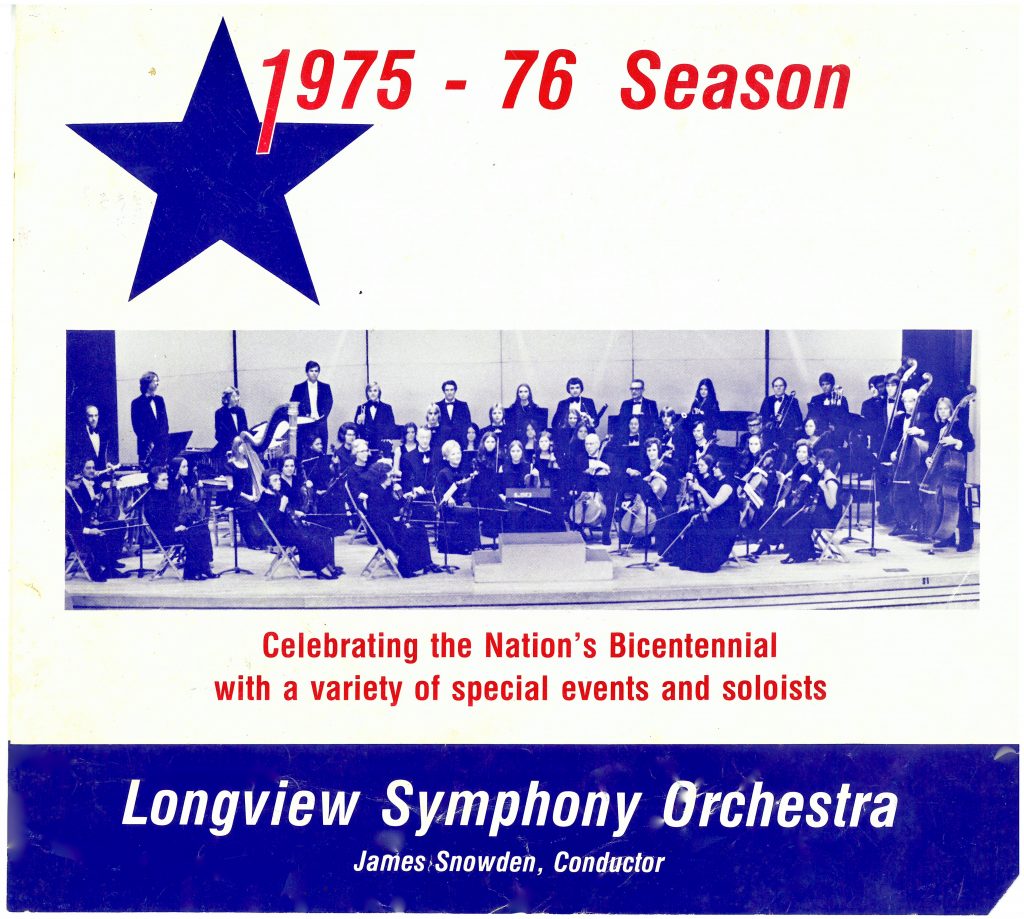

With the help and encouragement of my talented high school classmate Lynn Childers, combined with the shear impulse-of-will of James F. Keene, and certainly some Divine intervention, I found my way to East Texas State University (now Texas A&M University Commerce). Then, once again with Mr. Keene’s help and the support of other influential mentors such as Neil Humfeld, James Deaton, Gene Lockhart, Deanne Gorham, Bob Houston, and others I managed to apply for and receive the Basic Equal Opportunity Grant (the Pell Grant now) that made it possible for me to become a college graduate.

I was not the first person in my family to attend college. My uncle George graduated from the University of Houston and worked for many years with NASA as Chief of Maintenance Control for the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. Neither was I the first to receive a doctorate. As an automobile mechanic, my grandfather was awarded the “Doctor of Motors” degree. The certificate was proudly displayed in our house when I was growing up and I wish I still had it.

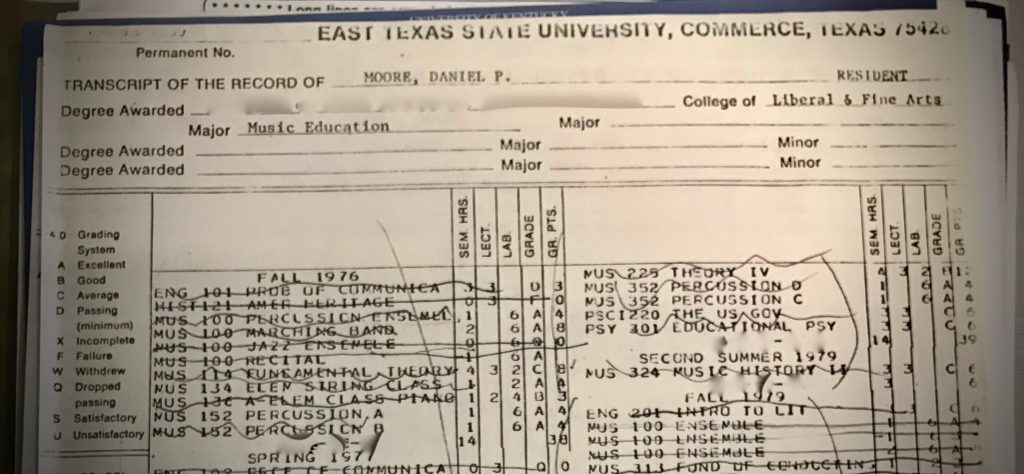

At college I threw myself fully into the study of percussion but from an academic standpoint, college would still be a challenge. Almost immediately in the Fall of 1976, HIST: 121 American Heritage became the bane of my existence. After flunking the course that Fall, then again in Spring 1977, I decided to give history a rest because it was clearly not my thing. The 7 a.m. class time might’ve had something to do with my spotty attendance record but who can say for sure?

I just couldn’t get the hang of things academically until two landmark events: the arrival of the blonde-haired clarinet player from Arkansas, who continues to inspire me to do better and be better, and meeting Dr. Frank Barchard, who was not, to my knowledge, a musician but a historian.

Dr. Barchard came to E.T. in 1965 as an Instructor of History, and officially retired as Professor Emeritus in May, 1995. He continued to teach at Texas A&M University Commerce through Spring semester of 2000 and passed away in 2002. He held offices in the Commerce Humane Association and the Rotary Club, and was a regular volunteer for the Presbyterian Hospital Auxiliary.

Dr. Barchard taught European History and was also Assistant Dean of the College of Liberal and Fine Arts. He was the sort of person you never got to meet unless you were a history major or in trouble academically. The latter would be my designation. I was summoned to his office in the Fall of 1980 to try and figure out if I was ever going to be able to graduate. He had a copy of my transcript that he went through line by line, scribbling over the courses and grades that moved me closer to graduation and striking through those that didn’t. At the end, there were too many strike throughs and not enough scribbles, and Dr. Barchard was shaking his head.

On my third attempt I had passed HIST: 121 but HIST: 122 still lay ahead for my last semester. Dr. Barchard finally stopped shaking his head and told me that I was three credits short. Three credits that would prevent me from student teaching and possibly from graduating at all. With my grant running out, along with my resolve, I thought I might never finish school. But to my surprise he said “why don’t you add the 3-credit class I’m teaching this semester?” My response was something like, “let me get this straight, you want me to take an advanced European History course with a roomful of history majors when I can’t even make it through American History I in less than three attempts?” His response? “Yes.”

I joined Dr. Barchard’s, Age of Absolutism and Enlightenment seminar, in about the second or third week of the semester and tried to find my way to the back of the room. I had never been in an academic class with so few people. Hiding in the back wasn’t going to be easy. “I’m in trouble” was my first thought: a premonition that soon turned out to be true.

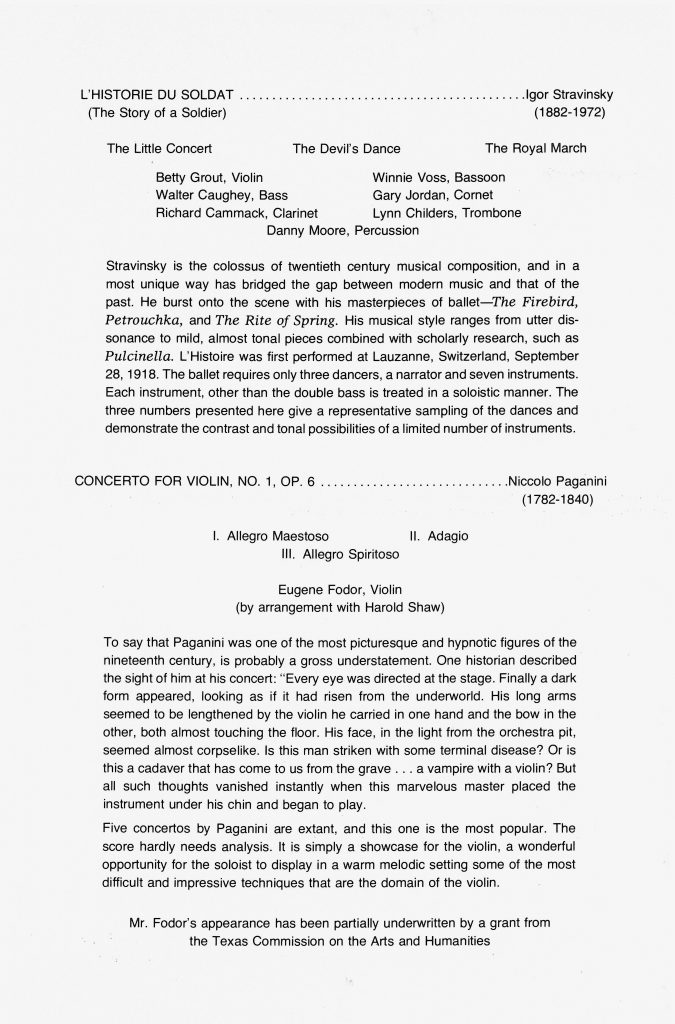

A few class meetings went by before Dr. Barchard decided to bring me into the conversation, a decision we would both soon regret. “Daniel, tell us what was going on in music during this period?” he asked. Awkward silence. Still he pressed, “you know: symphonies, opera, string quartets. Who were some composers from this period?” Me, thinking to myself: “I got nothing.” He knew I had already taken Music History and Music Literature*, so he tossed me a lifeline. “Well, if we are talking about the Classical Period in music, who were some of those composers?” Now, we’re both looking for the exit.

*It would be a few more years before I would come to fully appreciate what music history and literature professors Bert Davis and Gene Lockhart were trying to get across to me, but that’s another story.

Undeterred, Dr. Barchard continued; “Perhaps you are thinking of Mō… Mō… Mō…?” My brain stalled, churned, then suddenly lurched forward; “Mozart! Yes! Mozart was big! Really big!” Success at last. But while I’m certain everyone appreciated my insightful contribution to the discussion that day, I was just happy I hadn’t said Motown or Motörhead which was not outside the realm of possibilities from that period of my life.

Embarrassing to be sure, but it was a defining moment (certainly an important semester) because I finally began to understand the interconnectedness of Music, Music History, and World History. I thought, “I really should know more about this.” Who knew that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life and music were so heavily influenced by the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment? Dr. Barchard did, so why didn’t I?

It turns out that the principles of the Age of Absolutism and Enlightenment informed many composers from Haydn to Beethoven. In his opera The Marriage of Figaro, Mozart builds upon the themes from Beaumarchais’s play in which servants play the primary roles rather than simply providing comic relief—to be laughed at or mocked. They were equally as important to the story as the aristocrats.

I began to recognize the importance of knowing more about the music you play than just how to “hit all the right notes.” It also helped me understand why Dr. Davis kept referring to paintings and other great works of art during his Music History lectures, and why Professor Lockhart insisted we recognize the significance of world events in the creation of music. Knowing more about the sociopolitical environment in which composers lived and worked could help performers better understand how to interpret their music. Who knew? Evidently everyone except me.

Because of an evolving attitude about history, I passed Dr. Barchard’s course and then followed up with the second American History course. OK, I got a C, but my transition to a curious scholar didn’t happen overnight! Dr. Barchard’s class was the beginning of a journey that included making the Dean’s list in my final semester at E.T., then earning a 3.83 GPA in Grad School (Wichita State University) and culminating with a 4.0 in the doctorate (University of Kentucky). It also sparked a lifelong interest in learning and appreciating the history of things.

This was all because Dr. Barchard, and the entire faculty of the Music Department at E.T., took an interest in helping me help myself, each in their own inimitable way. The next time we sat down to do the strike throughs and scribbles, Dr. Barchard finished, stood up, shook my hand, and congratulated me on my upcoming commencement.

Unfortunately, Dr. Barchard passed away a few years before I would be honored by Texas A&M University Commerce as a Distinguished Alumnus (2005). I wonder if he saw THAT coming? Even if he hadn’t, I think he would’ve been proud of the part he played in getting me from there to here!

I will always appreciate Dr. Barchard, and remember the day I became a student of history.

Recommended Listening:

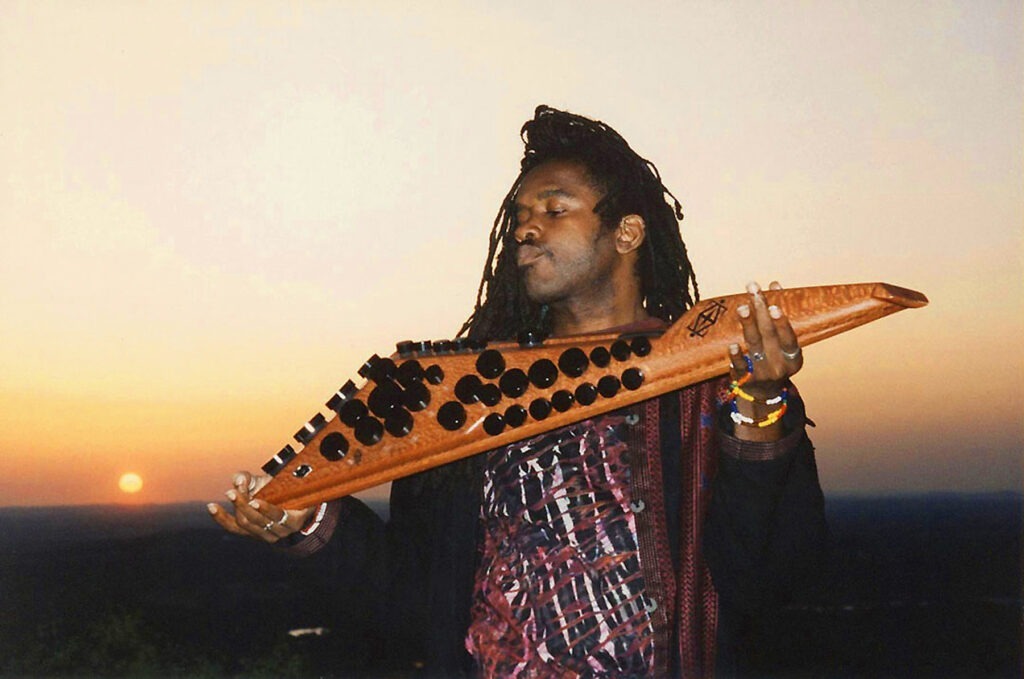

Andante from Mozart Piano Sonata No. 16 performed by Dan Moore on marimba.