Yesterday marked the second year of the passing of my mentor and friend Dave Samuels, and since Facebook Notes have gone the way of the dodo, I thought I would update and repost this remembrance to my new blog page.

Not long after receiving a text from Mat Britain that Dave had passed away, I began to see the many condolences and remembrances of him appearing on social media. And even though he had been in decline for several years and was no longer in the public eye, it still came as a shock. I guess these things always do.

The last time I spoke to Dave, I couldn’t be sure if he really knew who I was, but at the same time he still retained the same dry wit and mordant humor that endeared him to (or sometimes alienated him from) people. I considered the possibility that this moment might be the last I would share with him. That fear was later confirmed to me by his longtime friend and duo partner David Friedman.

One of the most heartwarming developments in the weeks following his passing was seeing all the photos of Dave posted online. In every shot he graciously stood there smiling sincerely, arm in arm with mallet players both accomplished and amateur, and with fans from around the world. Everyone, it seems, had a picture of themselves with Dave Samuels. Why; because he was a talented and respected musician who performed a lot, played on many excellent recordings, won a couple of GRAMMYs, gave countless clinics and masterclasses, wrote beautifully crafted music, and inspired more than a few generations of vibes/marimba players? Yes, but it was more than that. He always took time to meet people, talk to them, make them laugh, advise them, or just pose for a picture, and here were the stories and photos to prove it.

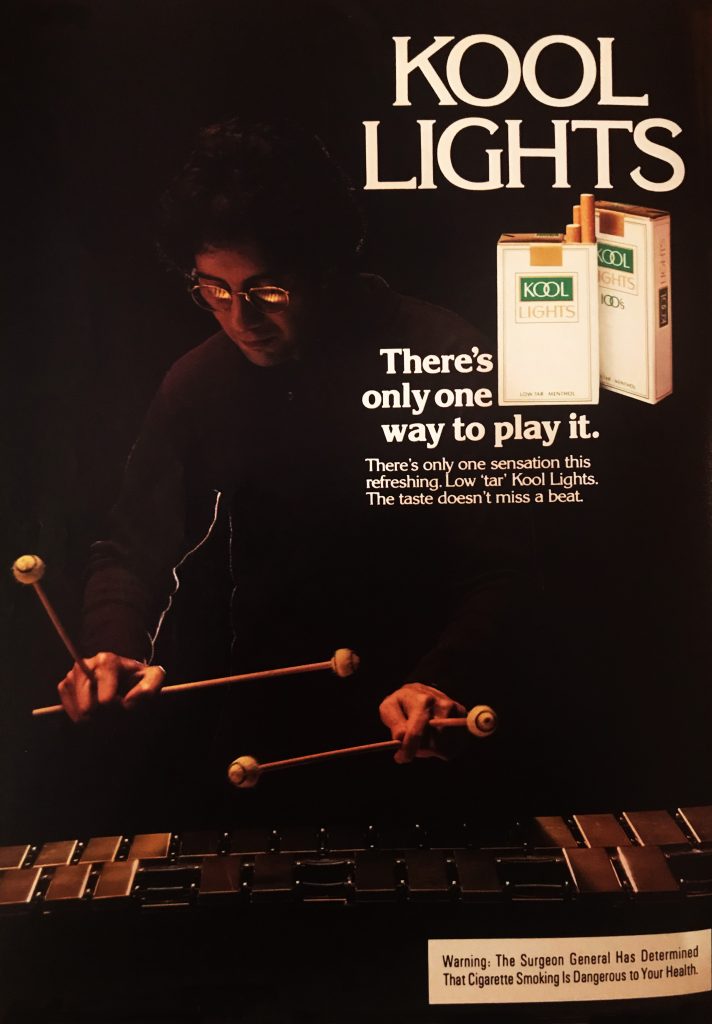

I always admired Dave for taking the marimba to the big stage of popular, jazz, and Latin music; first with Spyro Gyra, then with the Caribbean Jazz Project along with Andy Narell and Paquito D’Rivera. In 1979, Spyro Gyra’s Morning Dance was a Top 40 Hit and a #1 Hit on the Adult Contemporary Chart. The recording featured a marimba solo and a steel pan both played by Samuels (a detail that Andy Narell never let Dave forget). With Spyro Gyra, Dave Samuels brought the marimba to perhaps its largest audience. He was—pardon the expression—a Rock Star.

Mat and I once met Dave for dinner before a Spyro Gyra concert. We ate, talked, heard his latest jokes, and had a great visit. When we picked him up at the hotel he told us that he hadn’t actually been to the venue yet. As concert time approached he didn’t seem terribly concerned about getting to the hall. Finally, we headed to the concert arriving just minutes before showtime. We walked in the stage door and Dave casually glanced out to see the vibes and marimba set up with mallets carefully laid out and everything ready for him. We thought: “This is the big time; the kind of thing marimba players could only dream about.” Later we laughed about it—and aspired. He was one cool cat!

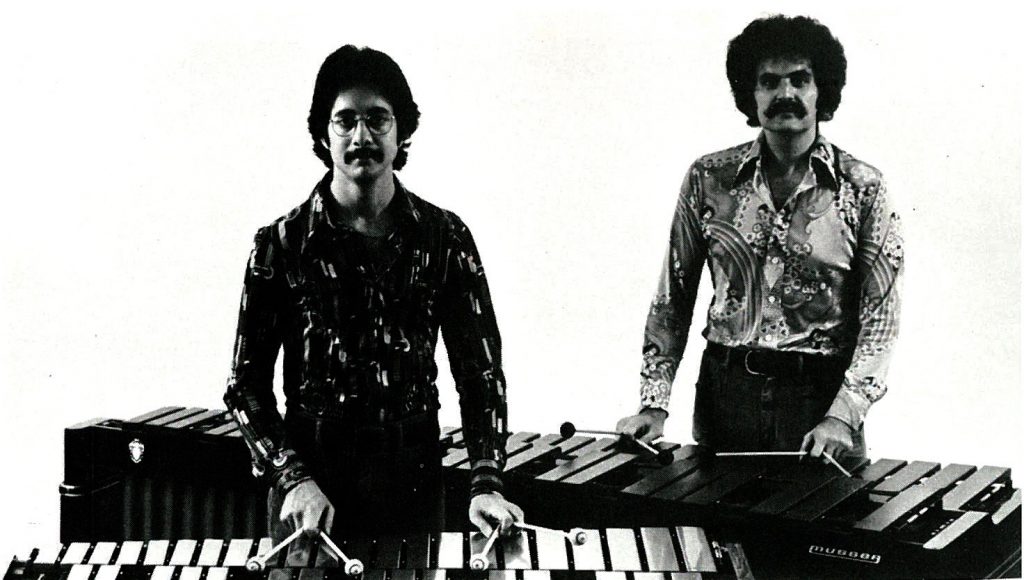

With their originative group Double Image, Dave Samuels and David Friedman defined the marimba/vibraphone duo genre. They showed us that you could, and should, be able to play both instruments well and that they are perfect foils for each other in creating rhythmic, expressive, and compelling music. They remained friends their entire adult lives and played together around the world, even into the last years of Dave’s life.

I took my first lesson with Dave Samuels in 1984 then continued to study with him off and on for about the next ten or more years (longer than with any other of my important teachers and mentors). I listened to his recordings, performed his music, transcribed him, wrote papers about him, composed music for him, and consulted him on some of my life’s biggest decisions. During a memorable visit to Iowa City in 2000 he advised my wife and me, at length, on the ins and outs of buying a house. He loved giving financial advice.

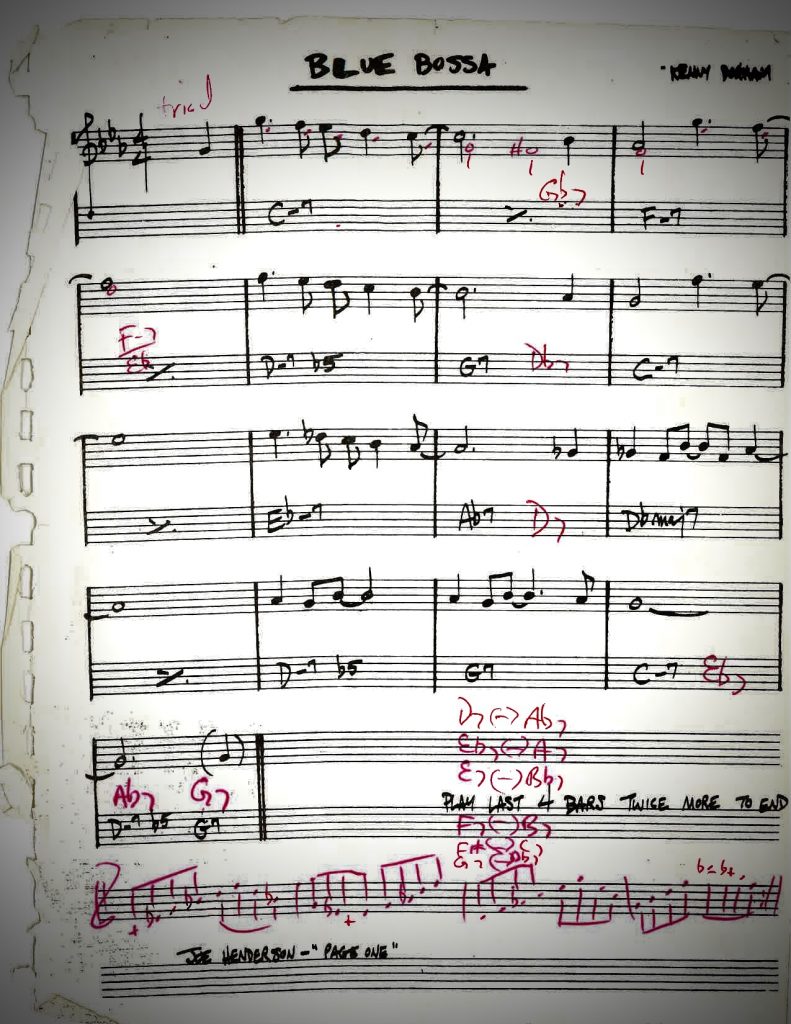

Dave was a demanding teacher who had little patience for anyone who wasn’t serious about learning. “Stop right now” he would interrupt; “what chord are you on?” “C minor 7” [replying sheepishly]. “No, you are in the turn-around and it’s a G7.” He knew I was faking it and that aggravated him. “Come on man,” he would say in frustration. “It’s just the same [stuff] over and over again.” But he could also be incredibly patient. If I asked him to show me a lick, he would stop and break it down slowly to help me understand exactly what he was doing.

Whenever possible I would sit, practically at his feet, with my eyes and ears positioned as close to the bars as possible (without getting hit by a flying DS-18 mallet). I was trying to absorb as much music from him as I could by any means possible including osmosis if necessary. I’ve watched him from the wings of Spyro Gyra shows, Double Image concerts, and in many other settings including once with a surreal combo of hempen homespuns playing jazz standards in a Cowboy Bar in Livingston, Montana. True story. Over the years we played together both privately and publicly and I always learned something new every time.

When the Britain Moore Duo was just starting out, Dave and steel pan artist Andy Narell became encouraging and supportive mentors. We had many memorable Duo lessons with Dave that helped shape the BMD. On one particular occasion, Mat and I infamously hauled our marimba and pans into the lobby after a Spyro Gyra concert to have a lesson with him. We played our hearts out while the crew noisily broke down the band’s gear. We worked until the stage grew dark and quiet then he stopped suddenly, glanced at his watch, said “later cats” with his familiar droll inflection, and disappeared into the tour bus that was waiting just outside the theater doors. No goodbye, no hugs or handshakes, just an implicit promise that we would indeed meet again—later.

By the time the bus door closed behind him with a final “cussshh,” it was well past midnight and pouring rain. As they pulled away, we were left standing agog in the lobby and with the theater staff telling us to get our stuff and get out! We didn’t sleep much that night as we tried to dry out our instruments and process everything that had happened over the course of one weird, wet, and memorable evening. We wanted to remember everything he told us to work on and make it better by the next time “later” rolled around.

But in all that time, over all those years, and given many opportunities, Dave never once told me “good job.” That just wasn’t his way. To study with Dave, you had to bring your own self-confidence, no matter how paper thin it was. He never let on that you were on the right track. You had to know that if he didn’t think you were worth his time and effort, he simply wouldn’t continue to teach you. After a particularly frustrating lesson I asked him: “Am I going to make it?” He snapped back; “I can’t tell you that; nobody can.” Speaking about his students in an interview for Modern Percussionist Magazine he said “[t]hey’ve got to teach themselves. Ultimately you are really a guide more than you are a teacher. I feel responsible for showing my students ‘how to,’ but I don’t feel responsible for how far their innate abilities may take them” (Mattingly 11). Well, I can attest to that. It was up to me to figure out—using the same logic—that neither could anyone predict that I wouldn’t make it!

There were however, subtle hints that you were in the hunt. If he complained to you that someone else’s performance “wasn’t so nice” or that their clinic “didn’t tell me anything new” then you knew his expectations for you were higher. There was an assumption that you had reached a certain level but it was never spoken.

When Mat and I started gaining traction as the Britain Moore Duo, we ended up on the bill with Dave on several Day of Percussion events. After one such event, Dave and I talked late into the night about how disappointed he was in his own performance that evening. Opening up to me in that rare unguarded moment allowed me to know that he respected my musicianship enough to reveal this to me. I remember thinking that “if this is how hard he is on himself, then how could I expect him to let me get by with substandard playing?” It made me want to work even harder.

When I stopped studying with Dave, it wasn’t because he never complimented me, but because someone else did. After a Britain Moore Duo concert, an audience member approached me and gushed; “Man! You sound great (the words every musician loves to hear). He continued, “you play just like Dave Samuels!” (cue sad trombone sound) That was the end of my lessons with Dave; or at least it was the beginning of the end.

One reoccurring theme in my interactions with Samuels was the importance of finding one’s own musical voice. He didn’t want the Britain Moore Duo to play the music of Gary Burton and Chick Corea (a lesson we never quite learned*), or Double Image, or any other established group. He would say “you don’t want direct comparisons with players like that.” It stung a bit but we—at least mostly—got the point. He encouraged us to write our own music and to use it to mark our musical territory. Being told that I sounded like Dave was a compliment to be sure, but it pushed me toward the realization that I needed to focus more on creating my own sound; my own voice.

*Some Lessons You Never Learn: Maybe That’s OK—Chick Corea (1941-2021)

Since Dave’s passing, I will be teaching a lesson, and find my thoughts returning to him. I hadn’t realized before how many of his pedagogical concepts I use every day. I’ll be working on improvisation with a student when a Dave-ism finds its way into the conversation. My teaching style today though is different than Dave’s. I have found value in both criticizing and complimenting. Maybe it’s emblematic of the times we live in or maybe it’s just my style, I don’t know, but I always encourage my future educators and band leaders to “start by saying something positive before moving on to criticism.”

I still get perturbed when my students don’t do their best and I don’t hesitate to let them hear about it. The best thing that can happen as a student is to reach a point when the teacher becomes comfortable enough to transcend the “niceness” of someone who is clearly trying to avoid hurting your feelings. Honest constructive criticism is the only thing, outside of your own desire, that can help you be a better musician. Samuels’ approach during our early lessons was to say little or nothing meaningful. But when we finally got to know each other well enough, and he decided I was serious, the gloves came off and he began to tell me what he really thought—often at the expense of my bruised ego—and that’s when we began having the most productive sessions.

Compliments you can get from your friends, family, and adoring fans but genuine helpful criticism can only come from a teacher who cares enough to give you the feedback you really need to hear at the moment you need it most. But for that to happen, you must be willing to allow your self-esteem to lose some steam.

Maybe Dave’s teaching style worked for me because I was not going to be deterred from my musical goals by anyone. But it did work, and I am grateful for that. I should’ve told him this before he left us, but I didn’t, and that I regret. So, if he were alive today I would sit down and write a letter that might begin: “Dear Dave Samuels, thank you for never telling me ‘good job.’”

In Memory of Dave Samuels

October 9, 1948 – April 22, 2019

Works Cited:

Mattingly, Rick. Modern Percussionist. Vol III Number 1, 1986-87.

Update: Since Dave’s passing, his archives have been donated to the Berklee College of Music and to the Center for Mallet Percussion Research in Kutztown, PA. Before the Pandemic lockdowns, I began working through the 10 banker’s boxes of music, 4 boxes of framed posters, album art, and awards, and other materials given to the Center for Mallet Percussion Research. It has been fascinating and enlightening to see many of Dave’s works in different stages of development and in manuscript form. Look for more about the Samuels collection at the CMPR in the future.