Back in the day LP record albums ruled the musical world and most every musician aspired to release their music on this prestigious format. If you got on vinyl, then you could feel like you had arrived as a legitimate musician. A lot has happened in the music industry during my lifetime, and it makes me wonder if history really does repeat itself. Read on if you want to hear my side of the story…

I began my journey into music recording in 1972 when my neighbor and best friend was gifted a 4-track reel-to-reel tape recorder. I was learning to play drums and Mark (who was a couple of years older) played 12-string guitar and sang. We had endless fun creating artsy-jazzish-moody-nerd-rock inspired recordings in his living room then forcing our friends and family to listen to the result. Come to think about it, that hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years. Even back then we aspired to be recording artists and maybe one day put out an LP.

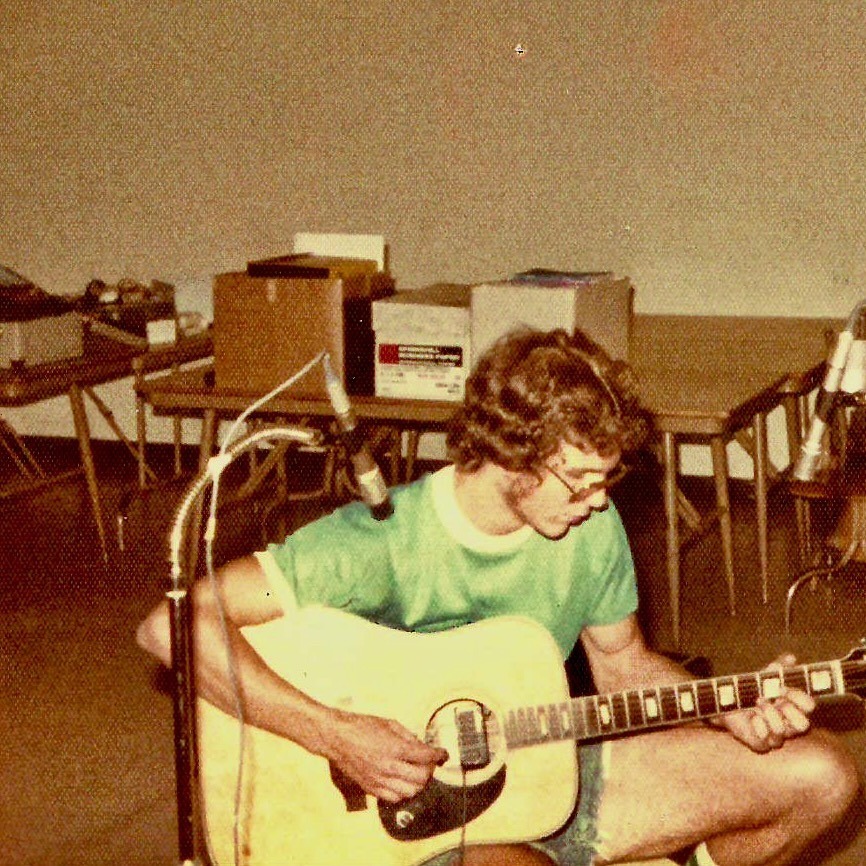

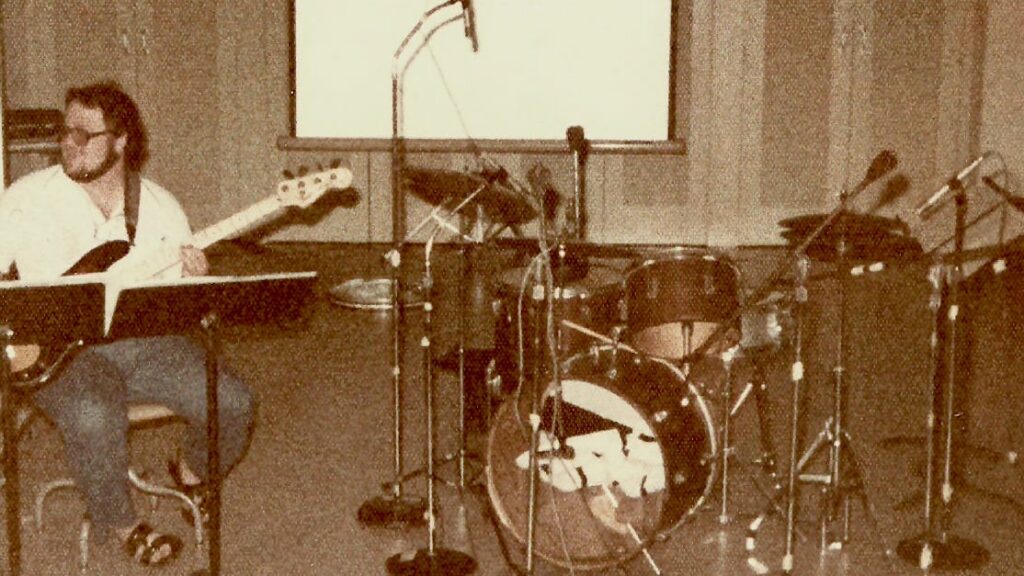

By high school I was composing and arranging music for my friends to record in elaborate sessions in the high school band hall trying to emulate the sound of Chicago, Blood Sweat and Tears, Chase, Don Ellis, and other horn bands of the 1970s. This time the recording equipment was an 8-track reel-to-reel recorder owned and operated by my high school jazz band director, Gary Jordan, who was a big influence on my musical tastes.

My interest in composing and recording music continued to grow throughout my college years and into—so called—adulthood. One thing is sure; you will never forget the first time you mic’ed up a drum kit and heard the sounds of a recording session that you wrote, produced, and recorded with your friends coming from a nice pair of speakers.

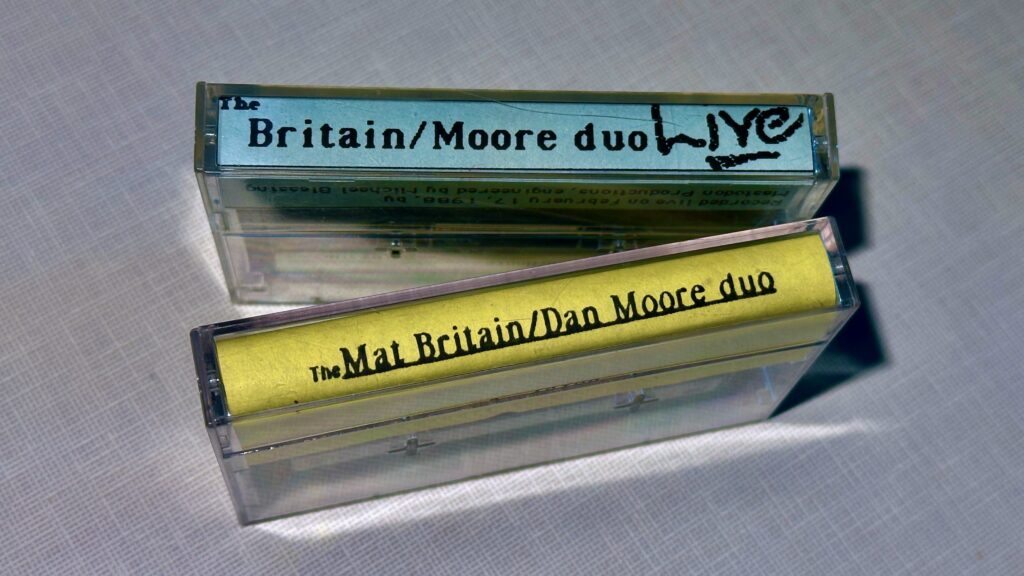

In grad school, I met another kindred spirit who was an aspiring steel pan player and was also interested in making recordings, Mat Britain. We made our first recording together in 1985 (on cassette tape) and we have continued to enjoy producing our best efforts on recordings for nearly forty years as the Britain Moore Duo. For us as twenty-somethings, recording studio time was expensive and stressful, so our budget always went to the studios. We certainly couldn’t afford to make an LP back then, so cassette tapes were the primary means of sharing our music.

In 1989 we finally bit the bullet and released a 4-song 12” Extended Play (EP) record. It was a major accomplishment for us to record the album (in two different studios), find a mastering engineer (whose lab looked like something from an episode of Star Trek) to create an expensive master and test pressing, and send the album for a costly duplication. It was quite a process and investment for a couple of broke musicians trying to make their way in the musical world, particularly considering how much we spent on tour outfits.

The EP (Extended Play) format allowed for longer but fewer tracks on each side of the record and seemed to be the best choice for the music we were trying to create at the time. There was no artwork other than the center labels. All we could afford was a simple black jacket and some stick-on labels that we added ourselves over the plastic wrap. When the record was opened, the fancy label was discarded along with the wrapper leaving only a black record jacket. Think Spinal Tap here: “It’s like how much more black could this be? And the answer is none. None more black.” —Nigel Tufnel

We were so proud of ourselves for this achievement but then, in what seemed like the blink of an eye, came the advent of the Compact Disc (CD) era. Now everyone was releasing CDs, and records were suddenly passé. We often joke that the Britain Moore Duo was possibly the last group to make a record! A distinction to be sure albeit a dubious one. We had finally made it to the big leagues, but the big leagues became the minors practically overnight.

We were assured that with CDs there would be no more scratches, pops, or skips, no wavering pitch, and the sound would be fully “digital” (not that old fashioned analog). DDD* was the wave of the future and to top it off, CD store employees would blithely toss a disc across the room, retrieve it, and pop it into the player to show how it could withstand the rough treatment that a delicate LP could never take. Many people responded with a resounding “sold! Take my money!” Everyone that is except die-hard analog fans who prophesied that digital was a cold and ultimately inferior product compared to LPs and would die a certain death in the marketplace of ideas. We weren’t so sure. Others warned us that digital was the “the future of music recording, and we better get on board or be left behind.” What to do next? Some research.

*“As digital audio continued to creep into the music production process, the Society of Professional Audio Recording Services (SPARS) developed a three-letter code to inform consumers. SPARS codes printed on records classified the recording, mixing, and mastering stages with an A for analog or a D for digital. Under this system, “AAD” denoted a digital remaster of an analog album, “ADD” indicated an album recorded on tape but mixed and mastered digitally, and “DDD” specified an all-digital production.” —Vintage King

The first CD and player I purchased was from a boutique record store in Bozeman, Montana. Flim and the BB’s recording Tricycle was the first jazz album to be recorded, mastered, and delivered entirely in the digital domain. The recording chain, after the first few feet of microphone cable from the musicians’ instruments, remained in the digital domain until it was decoded by the consumer’s CD player. According to Wikipedia, “the [Flim and the BBs) disc displayed the full dynamic range available in CDs, becoming a popular test disc.” I thought it sounded pretty good and started to think that maybe CD would be the next logical step.

in 1990, I went to Japan (where they always seem to be ahead of the technology zeitgeist) and bought one of the first-generation portable Sony CD players, the Discman. It was cool but not practical. It would jump and skip if you so much as looked at it. Even a record player could withstand the bumps and grinds of disco music and weed parties of the 1970s.

Cassette tapes continued to be popular into the 1990s because they were cheaper, easier to deal with, and more reliable than either LPs or CDs, which is why nearly every automobile in the country at that time came equipped with an AM- FM-radio Cassette player, even if the audio quality was, well, suspect!

Making and sharing mixtapes became a cultural phenomenon—a romantic art—that became an unfortunate casualty of the digital age. Writing for Forbes online, Michele Catalano opines that “the art—and make no mistake about it, it is an art—of making a mixtape is one lost on a generation that only has to drag and drop to complete a mix. There’s no love or passion involved in moving digital songs from one folder to another. Those ‘mixes’ are just playlists held prisoner inside a device. There’s no blood, sweat and tears involved in making them.”

After much discussion, the BMD made the leap to CD in 1993 when we released Cricket City on both CD and (of course) cassette (just to be safe). This release also launched my record label and publishing company Cricket City Music & Media which is now a certified ASCAP music publisher. At the time we thought $15 for a CD; are you kidding? Nobody is going to pay that kind of money when you could get a vinyl album for around eight dollars. According to the Inflation Calculator, $8 in 1990 would be around twenty bucks today and $15 would be worth more than $36 now. Regardless, everyone started buying CDs as records and cassettes began a steady decline.

LPs hung on until Napster delt a serious blow to their popularity, in addition to convincing an entire generation of young people that all recorded music ought to be available to them for free! Soon after, iTunes (arguably the bigger culprit) and other music streaming services doomed the LP (and possibly other formats) to the dust bin of history once and for all (well, not quite as it turns out).

One problem with LPs was that you could only put about 20 minutes of music on each side of an album and people longed for more. Truth be told however, these limitations forced musicians to make important and difficult decisions about the songs they would release.

The CD seemed unlimited with its 74 minutes of recording time. You could now put more and more music on one disc. This was a boon to classical music since you could fit most symphonies onto one disc without having to stop in the middle to turn the record over. Jazz musicians, who were constitutionally incapable of bringing in a tune in under six minutes, also embraced the compact disc for the same reason. But it did become a problem for some musicians because many felt obligated to include everything they recorded on the CD, even if it wasn’t that good. You wanted to fill that space, so some musicians struggled to get enough high-quality material, and it showed.

The Britain Moore Duo never once worried about running out of space on a CD. In fact, we too were more concerned that we weren’t filling the full 74 minutes when we probably should’ve been more interested in releasing our best tracks. From the beginning we were always trying to give the paying customer as much value for the dollar as possible. It was the same during the days of cassette tapes. We would rearrange the tracks on a cassette so there wouldn’t be more dead space at the end of side B than on the end of Side A. If you got a cassette that was out of balance, you felt cheated, and we didn’t want to shortchange our listeners.

Fast forward to 2024 and I’m nearing completion of a new solo recording—my first since 2004—and I begin to notice that more people are releasing and listening to records. Some just like having the large record jackets to hang as artwork on their dorm walls but many other college-age students own (and listen to) records—often raiding their dad’s record collection at home. So out of optimism, or perhaps vanity, I decided to release my new recording on CD AND LP.

But in considering an LP release, I found myself for the first time since 1989 having to make the same hard decisions that musicians of the pre-CD era had to make. I simply had too much material. And without going to the expense of a double LP (which is still a costly proposition) I needed to fit into the twenty-minutes-per-side LP format. This necessary editing process made the album better because I had to shorten tunes and cut others all together to fit on an LP. The result was—in my opinion—a tighter and more cohesive set of tunes that might have otherwise become tedious. Test mixes returned comments from people I trust that every track seemed too long, so I chiseled away at them until all that remained was the finished work of art. The influential American painter Hans Hofmann (1880-1966) would say this reduction is required “to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.”

The Long Way Home is a love letter to the people who have inspired and guided me on this wonderful musical journey I’ve been on since the heady days of those first recording sessions in Mark’s living room and the high school band hall.

If you long for the days of what my friend and colleague Damani Phillips describes as “concentrated ritual listening” that to me defines the LP experience, you might want to pick up a copy of The Long Way Home and immerse yourself in something that can only be experienced with a long-play vinyl record, a glass of wine, and a quiet room (perhaps with some nice headphones). YouTube star Mary Spender describes this as the sensation of “sight, sound, and touch” that are the hallmarks of engaging with vinyl record albums. I highly recommend her YouTube video on the subject.

At this point I have produced more CDs than in any other medium which makes sense for my demographic as a musician whose peak era of production was between 1980 and 2020. I am hopeful, however that I can extend my viability for at least a few more years (wink wink kissy face)! Between 2016 and 2024 I primarily produced recordings for my students including three solo recordings for DMA students and a recording of the Iowa Steel Band with steel pan legend Andy Narell. I even managed to release a 30th Anniversary re-mastered version of the Cricket City Album. But I’ve got more gas in the tank and (thankfully) no shortage of ideas for future projects including a new Britain Moore Duo album and a steel band recording with steel pan virtuoso Victor Provost just to name two. 2025 should be another busy year in the recording studio! And I am thankful.

For now, I hope you will join me for a shared experience of my long journey home to vinyl as you listen to The Long Way Home on LP or CD if you prefer, or—at the uttermost end of need—on Spotify. I won’t judge.

The Long Way Home is available for purchase on LP, CD, and Digital formats here:

Danmoore.hearnow.com

One more thing, before we go:

As a musician, I’ve journeyed on trains, planes, boats, and busses, around the world and back again, but my preferred mode of transportation is driving. I spend a lot of time behind the wheel heading to the next gig. It gives me plenty of time to think, and plan, and sometimes even to compose when the mood is right. But for me, the longest part of any journey is the one to return home, and that’s what The Long Way Home is about.

This recording is also about friendship and family because the music would not exist without these elements. This album is dedicated to the memory of Dave Samuels (1948-2019) a great teacher, mentor, and friend; to the memory of Chick Corea (1941-2021), a kindred spirit of marimba players; in honor of the renowned vibraphonist Gary Burton’s retirement from performing; and like everything I do, this is for Liesa.

Thanks to Mat Britain, Orlando Cotto, Christopher Jensen, Jean-François Charles, Scott McConnell, Wesley Morgan, and Peter Naughton for lending their estimable talents to this project. Thanks to David Skorton for always listening and for letting me record his tune. Special thanks to James Edel for the ears, advice, cooking tips, and tech support. Thanks to Mike Tallman of Add Noise Studios for his thoughtful album design, and very special thanks to Dick Schory, one of my greatest mentors who celebrated his 93rd birthday just a few days after the album was released.

Citations:

Clip. “How much more black could this be?” This is Spinal Tap, 1984

Contributor. “The Early History of Digital Recording” Vintage King.com

Catalano, Michele. “The Lost Art of the Mixtape” Forbes online, 2012

Spender, Mary. Vinyl — The Future of Music? YouTube video, 2024

About Hans Hofmann