“The moon is full, and there is not a cloud in the sky. No stars are visible because of the deep white glow of the moonlight on the snow, which triples the ambient light and makes it possible to drive without headlights on these back roads. . ..” —Hunter S. Thompson, Generation of Swine “The Dim and Dirty Road”1

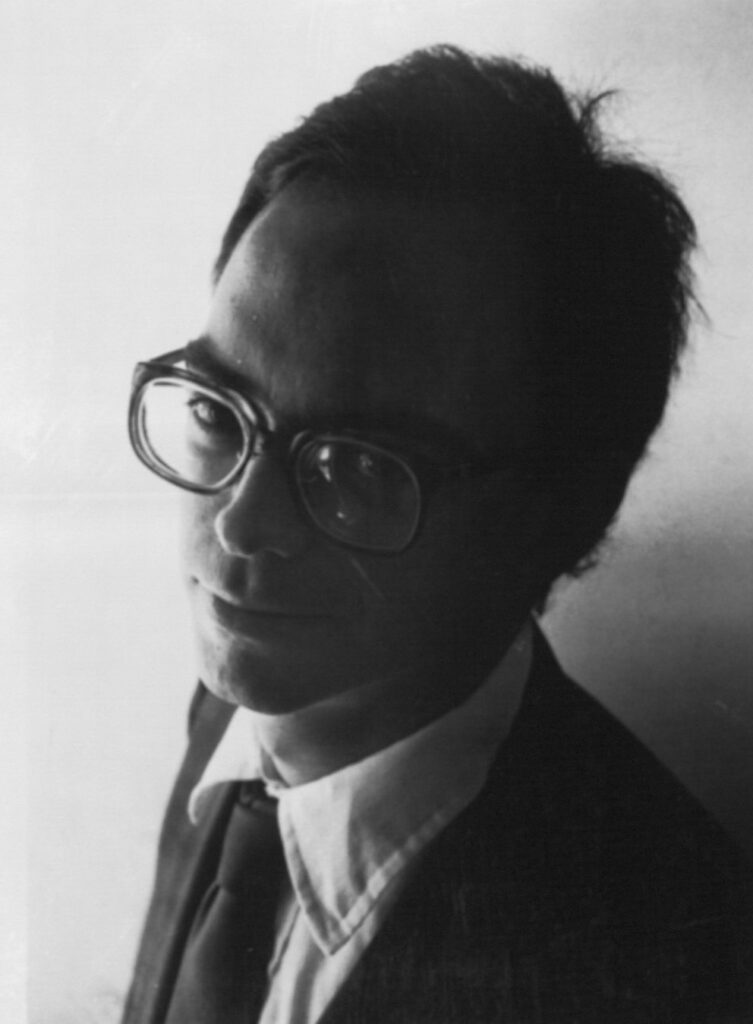

Composer, banjo player, folksy philosopher, and my dear friend Paul Iserman Elwood died February 2, 2025, after a year-long battle with glioblastoma, an incurable form of brain cancer. He had survived other attacks to his body over the years, but it was the assault on his creative and deeply contemplative brain that would be his undoing.

Paul loved to improvise and spent much of his life in that pursuit. As a composer (described as improvising in slow motion) and an improviser (composing in real time) it is not surprising that he found a musical metaphor in Thompson’s words.

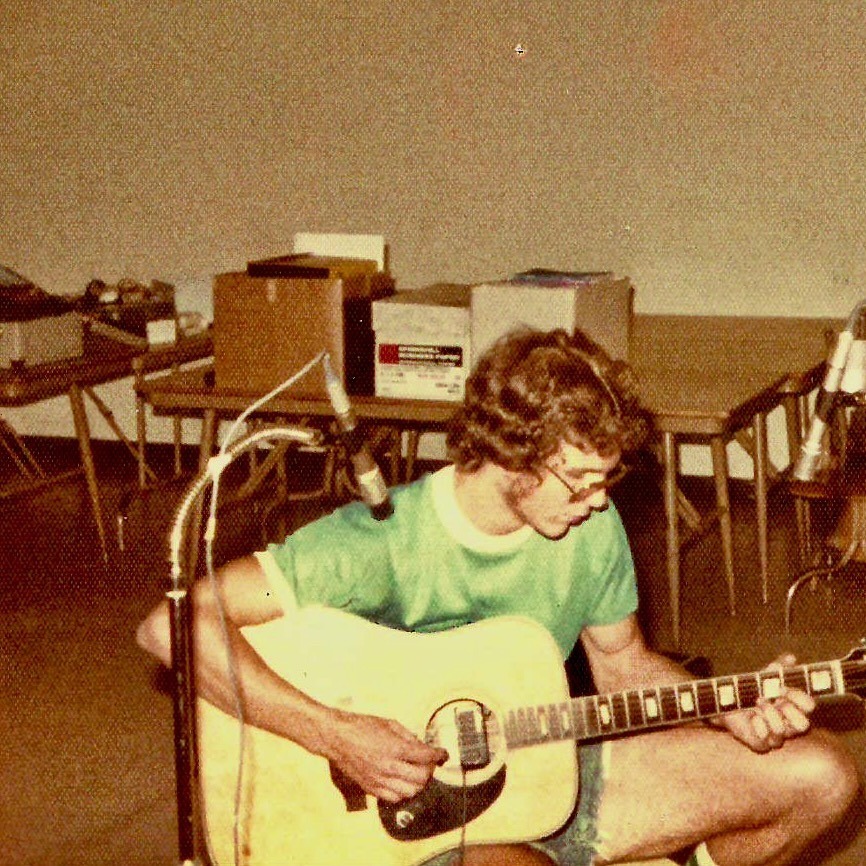

I met Paul in 1984, not long after arriving in Kansas for Grad School at Wichita State University. He was the craziest, goofiest, banjo-playing-avant-garde composer I had ever encountered (if you don’t count Edwin London in the 1970s who I don’t believe played the banjo). We were kindred spirits—equal parts musical misfits, ducks out of water, and chronic sufferers of imposter syndrome. We were both 26 years old—born in 1958—and searching for our place in the musical world. We became instant friends.

I came to Wichita State as a marching band Teaching Assistant thanks to my work as a drum instructor for the Sky Ryders Drum and Bugle Corps of Hutchinson, Kansas, just over 50 miles from Wichita, so my reputation somewhat preceded me. Percussionists at WSU, however, were unimpressed. Walking into the percussion studio for the first time, I was greeted by a message scrawled on a chalk board in large letters reading, “who is this Daniel Moore guy anyway?” My first thought was “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” which seemed appropriate except for the fact that I WAS in Kansas, but you get the idea.

What I found at WSU was an incredibly creative place thanks to inspired musical mentors like professors J.C. Combs and Walter Mays, as well as a group of talented classmates many of whom would become shining stars in the musical firmament and have remained my friends to this day. There was so much creative energy at WSU that if you had a new composition, you could walk from one end of the music building to the other and before reaching the back door you could assemble a group of outstanding musicians ready to play your new piece—whatever it was.

Paul took advantage of this moment in time and as luck (and I mean that sincerely) would have it, Paul scooped me up in his net to play his newest composition Snow Falls Ceaselessly (1984) for flute, cello, keyboards, and percussion with dancers, a hand signer and audience players. It was like nothing I had ever been involved with in my life, and I loved it. Saying “yes” when Paul walked by on that Fall day changed my life.

As an undergrad, Paul studied composition with Walter Mays (1941-2022), a Pulitzer Prize nominated composer and prominent teacher who was a significant influence on his development as a composer. Then he was propelled further into the avant-garde after a week of interaction with legendary composer/philosopher John Cage. In an interview Paul said that “He [Cage] gave lectures, he did rehearsals. Monday morning, I was in the first piece that he rehearsed, it was for three conch shell players with shells filled with water that we moved around and every now and then a bubble would surface and could be picked up by a mic. That was the piece, it was called ‘Inlets.’” 2

As I got to know Paul, I learned that he had a multifarious life; one as an avant-garde composer, another as a performing percussionist, another as a music teacher of children, and still another as an excellent banjo player and Bluegrass musician. Paul had already won the title of Kansas State Bluegrass Banjo Champion before heading off to Texas to study composition with influential composer Donald Erb at SMU. But it was this dichotomy that troubled him for many years as he navigated the choppy (read: snobby) waters of a musical elite that valued conformity over creativity and the diversity of ideas.

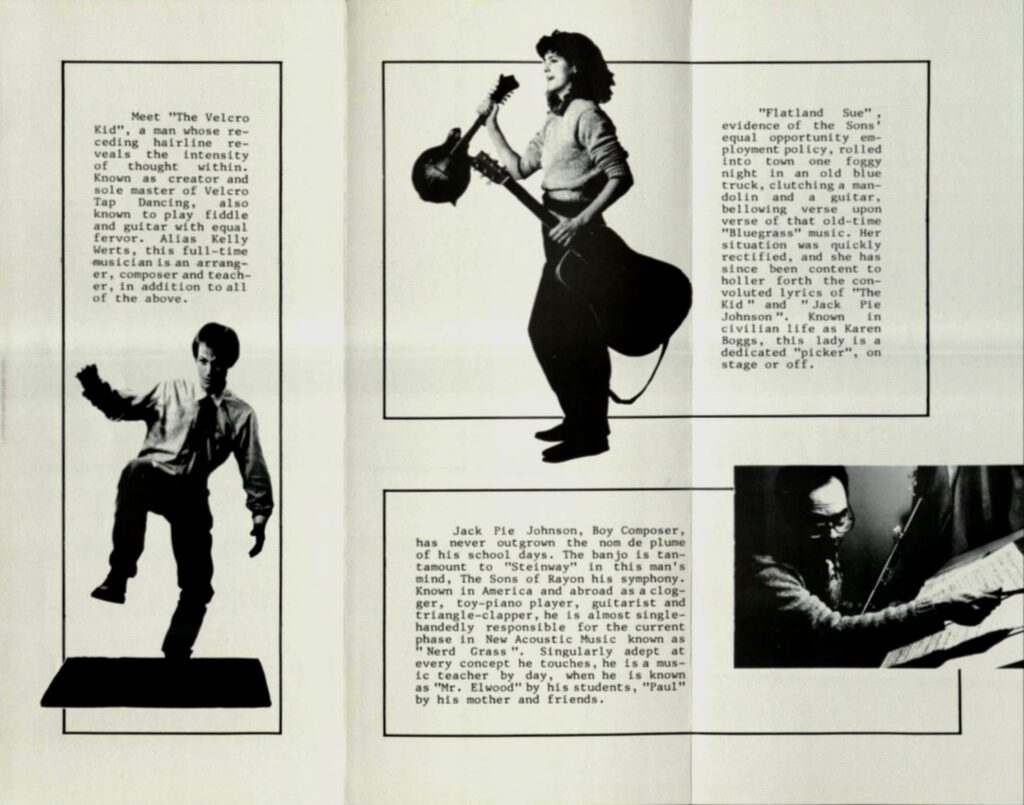

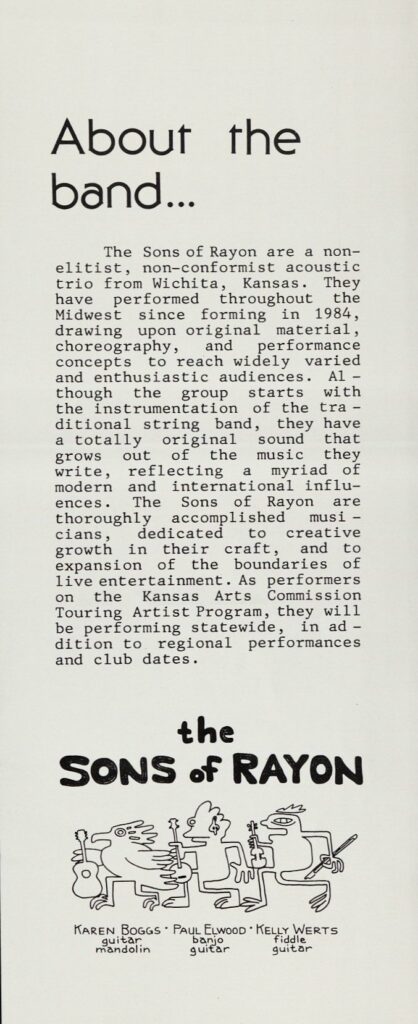

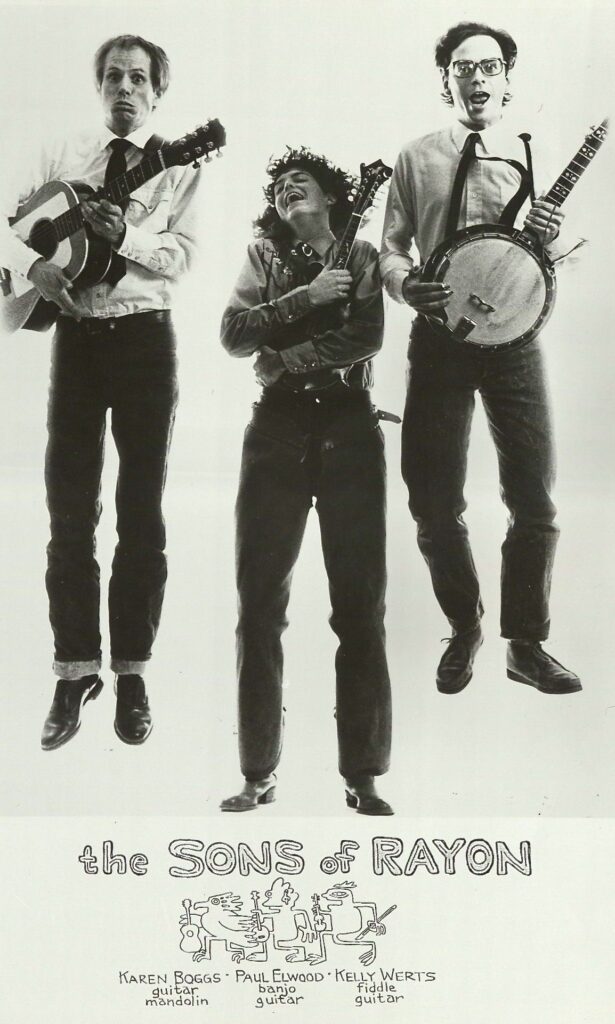

Paul always saw himself as an outsider. In a 1985 interview he said, “I can’t seem to fit into any group at all.” Speaking of his alternative-acoustic-trio the Sons of Rayon he went on to say that “we consider ourselves nerds… we’re outcasts from the bluegrass crowd and outcasts from new wave. We’re not hip.” The interviewer, however, took issue with that characterization saying that “some might disagree. Their appearances draw a regular crowd, and they have a mailing list of about 200 people. …their music is the revenge of the nerds.”3 But they were hip; they just didn’t know it. More about the revenge of the nerds in a minute.

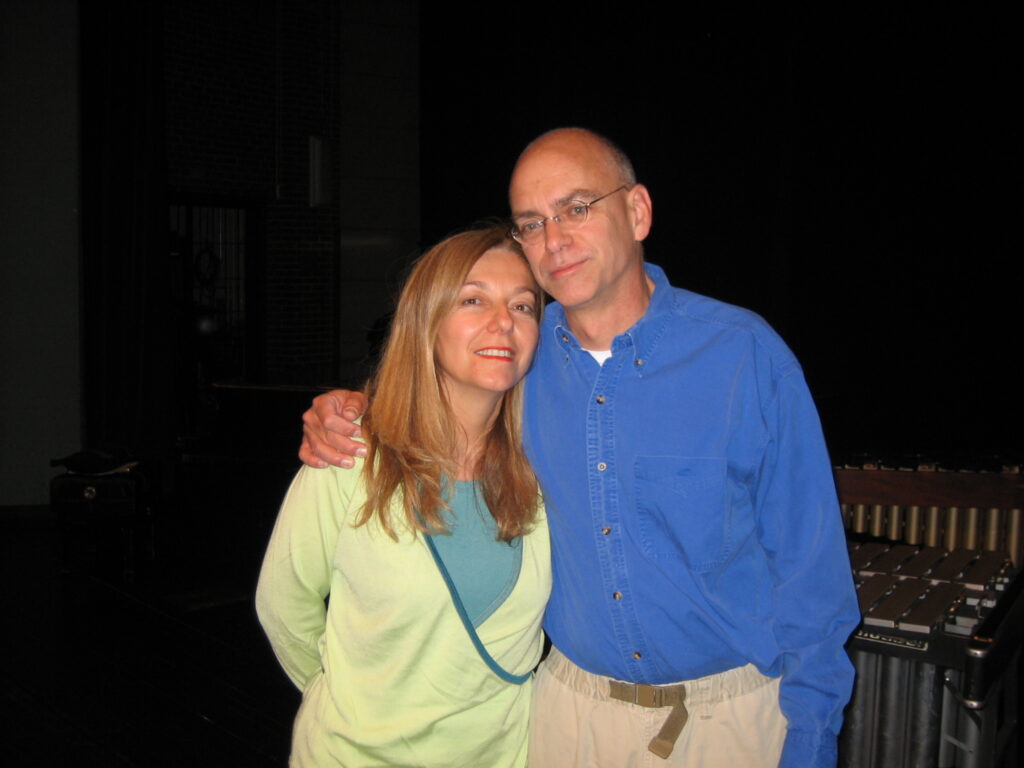

It would be years before Paul would come to terms with his life as both a serious composer and oddball musician. Perhaps it was finding confidence in himself with the help of the love of his life Régine Esposito. I like to think so.

It was a joy to be able to witness his evolution from disenchanted outsider to confident artist. I wrote a letter of reference for Paul for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Award every year from 2007 to 2023 and every year he was turned down. It was like one of the rhythms of my life; every December the phone would ring; it would be Paul wanting to catch up and asking me to write another Guggenheim letter. In 2023, he laughed and told me that, if nothing else, he hoped someday to hold the record for being turned down the most times. He never felt sorry for himself, even when he was sick. I think that is a far superior accomplishment.

Here is what I wrote in my 2023 letter of support for his last Guggenheim application:

“I have observed with great interest as Paul grew into his now mature musical voice as a composer. In many ways he is an outsider in contemporary music as a result of his refusal to be defined by current trends or the inherent conflicts between the life artistic and the career academic. Today I celebrate the resultant maturation of his singular compositional style and applaud his resolve to stay the course of his diverse artistic vision.”4

In 1984, it was perfectly preordained that Paul and I would meet when he returned to his hometown to teach music at Castle in the Air preschool and co-found the Wichita New Music Ensemble which (by the way) gave me my first non-school affiliated performance of one of my compositions. We were destined to meet and form a friendship that would last until his passing.

At WSU, our percussion teacher and mentor J.C. Combs was an imaginative impresario who despised much of the music written for percussion ensembles and he was open to new ideas for composition. In a recent interview J.C. said “I just wanted to do more creative things. I had been at WSU for about ten years, and I was bored with a lot of percussion music, so the projects sort of happened naturally as a way to keep myself and my students (and the audiences) interested in what we were doing. I also found that it was a great way to bring people in the community into the creative process.”5

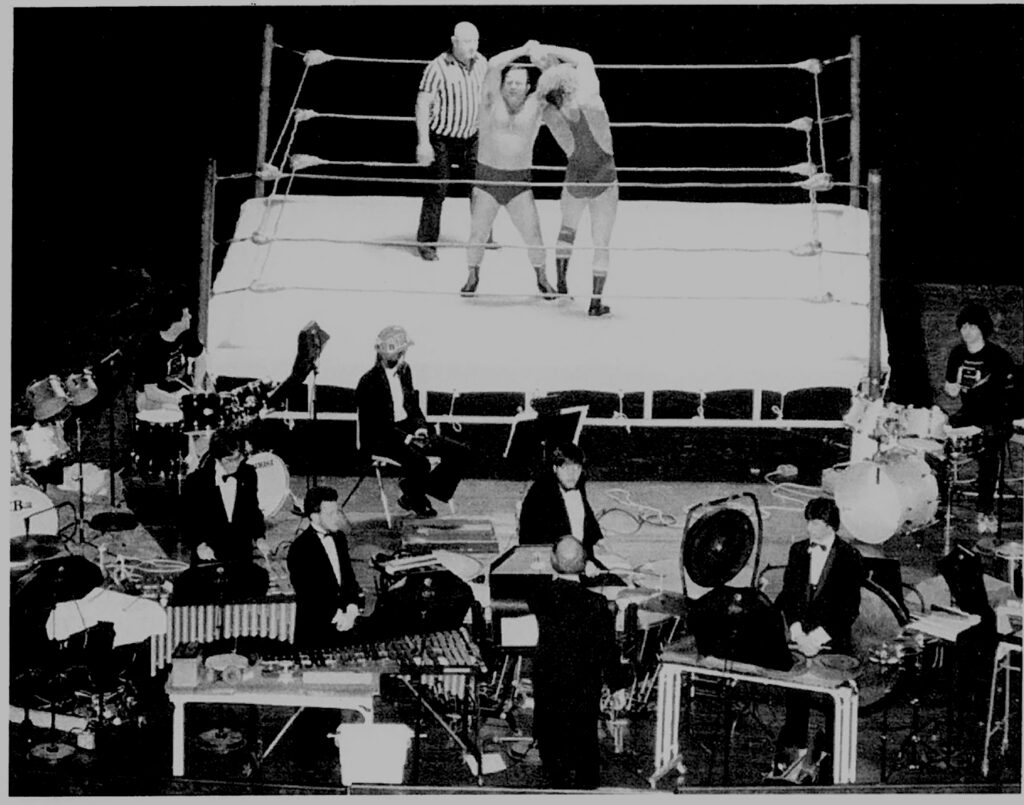

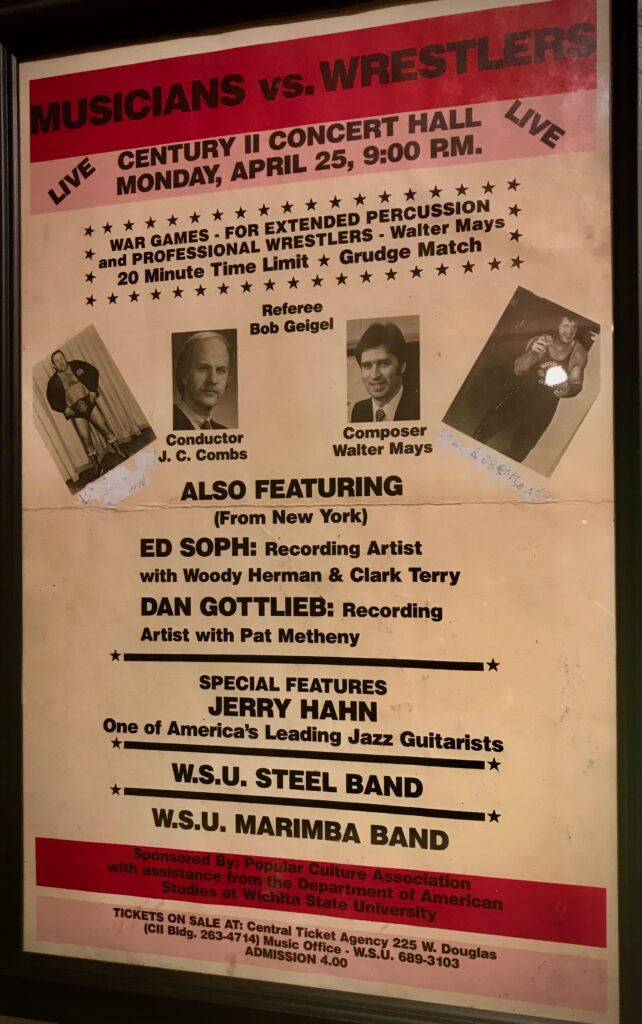

Combs and Mays had already collaborated on a major work that featured an “extended percussion ensemble” and included jack hammers, bowed Styrofoam, four drumsets (with no cymbals) and Heavyweight Championship Wrestlers. Yes, you read that correctly—wrestlers. *

So, the stage was set at Wichita for Paul to step in with his own brand of outlandish works for percussion ensemble that J.C. and his students took on with (occasionally guarded) enthusiasm. Dr. Combs once said that “creative things aren’t always without risk”6 and he, of all people, would know about risk. In a 1984 article for the Wichita Eagle-Beacon, arts columnist Don Grainger wrote that “it was the same J.C. Combs who starred in a locally produced motion picture about the decline and degradation of a music professor fatally addicted to pinball machines. The opus ended with an impressive bang when the student assigned to arrange a small explosion to indicate the end of the film overloaded the charge by a factor of (at least) three.”7

Paul’s music was certainly full of risks and I for one was ready to take them on. During my two-year tenure at WSU the percussion ensemble performed Under the Evening Moon for string quartet and percussion ensemble featuring folk musician, clogger/banjo player, Beverly Cotton; and Edgard Varese in the Gobi Desert for percussion ensemble and Velcro Tap Dancer Kelly Werts. Between 1983 and 1984 Edgard Varese in the Gobi Desert was performed at SMU under the direction of Deborah Mashburn, at WSU under J.C. Combs, and at Ithaca College under Gordon Stout. It was his first major composition, and a fascinating work that has been performed many times throughout the country.

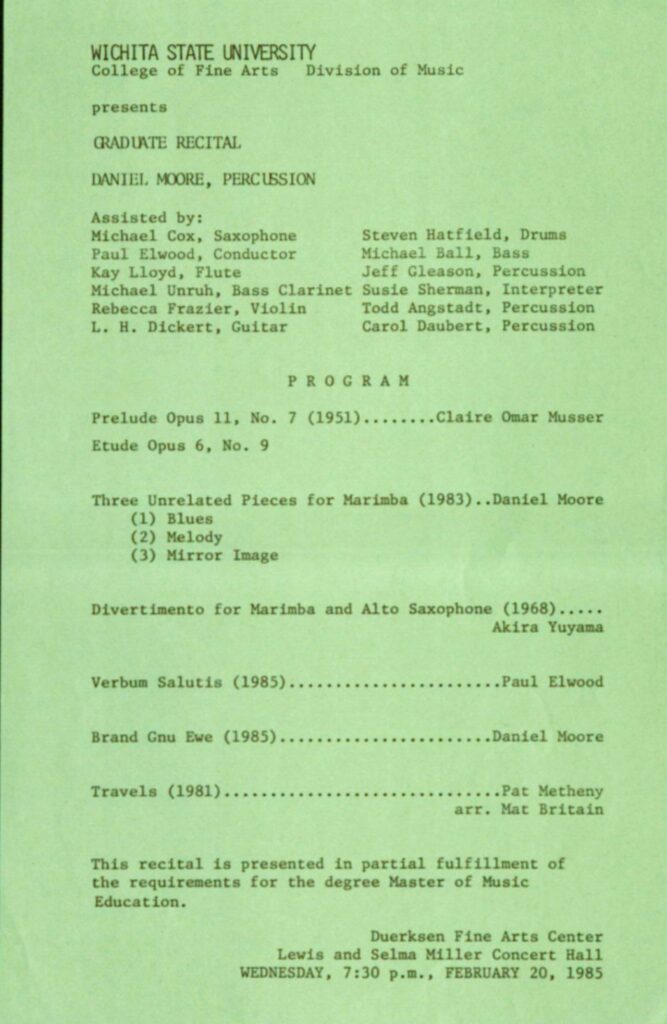

In an extraordinary burst of creative energy over an 18-month period, Paul wrote many new works for the WSU Percussion Ensemble, The Wichita New Music Ensemble, and for percussion degree recitals for his friends and classmates. During that time, Paul composed the afore mentioned Snow Falls Ceaselessly, Under the Evening Moon, and Edgard Varese in the Gobi Desert, as wells as Birds of Appetite for string quartet, Upon Waking in the Rear Arbor for brass quintet and solo percussion (for Gary Gibson and conducted by yours truly) Verbum Salutis for flute, bass clarinet, cello, percussion, and hand signer (for my Master’s Recital) and Roy Rogers Meets the Zydeco Kid, a radio drama starring Jack Pie Johnson (for percussion soloist Bruce Chaffin and three narrators). I am particularly fond of this piece as “Jack Pie Johnson Boy Composer” was Paul’s nickname and alter ego. The middle name “P.I.E.” of course stood for Paul Iserman Elwood.

I thought Paul was the coolest cat I had ever met, and I glommed on to him as quickly as I could. Even back then, I imagined myself becoming the prime interpreter of his work. He wasn’t sure he needed (or wanted) one at the time, but I was interested in—and fought for—the position none-the-less. I also fell in love with his self-described “Nerd-grass band” the Sons of Rayon.

In their promotional material The Sons of Rayon claimed to hold “the dubious honor of having re-invented the string band, with an eye toward the needs of a twentieth century audience. The three sons (one of which is a woman) experiment persistently with non-traditional ways of combining the traditional sounds of their acoustic instruments. With three-part vocals recalling the ‘high and lonesome sound’ of old-time singing, their modern original arrangements retain a classic balance of old and new.” They go on to say that “the group also reflects the more recent innovations of the psychedelic Sixties on through to New Wave of the Eighties. …Add to that, flavors from India, Africa, Ireland, and Mexico, and you have a truly eclectic ensemble.”8 In my opinion, this doesn’t even begin to describe the Sons. I was besotted every time I heard them perform.

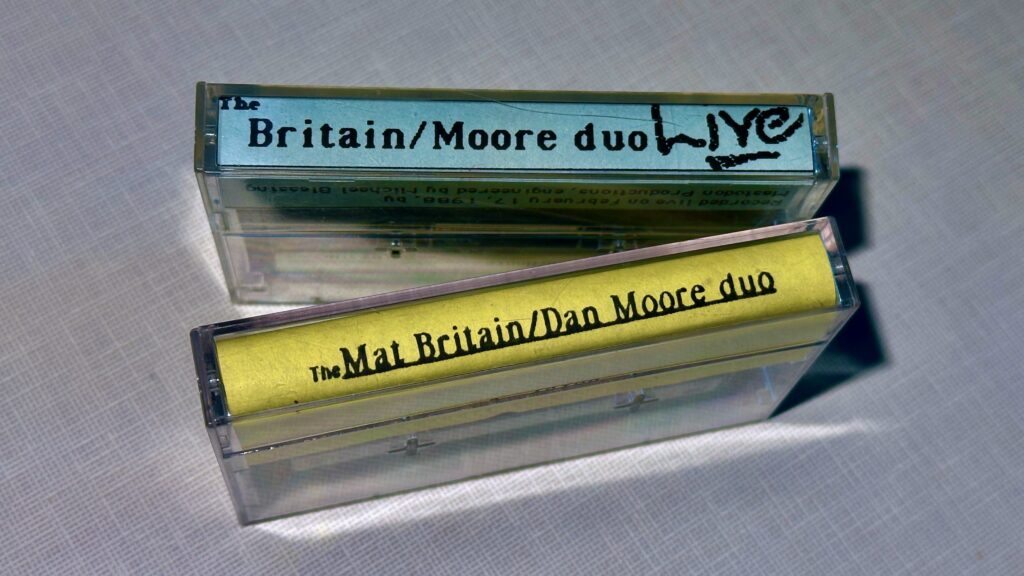

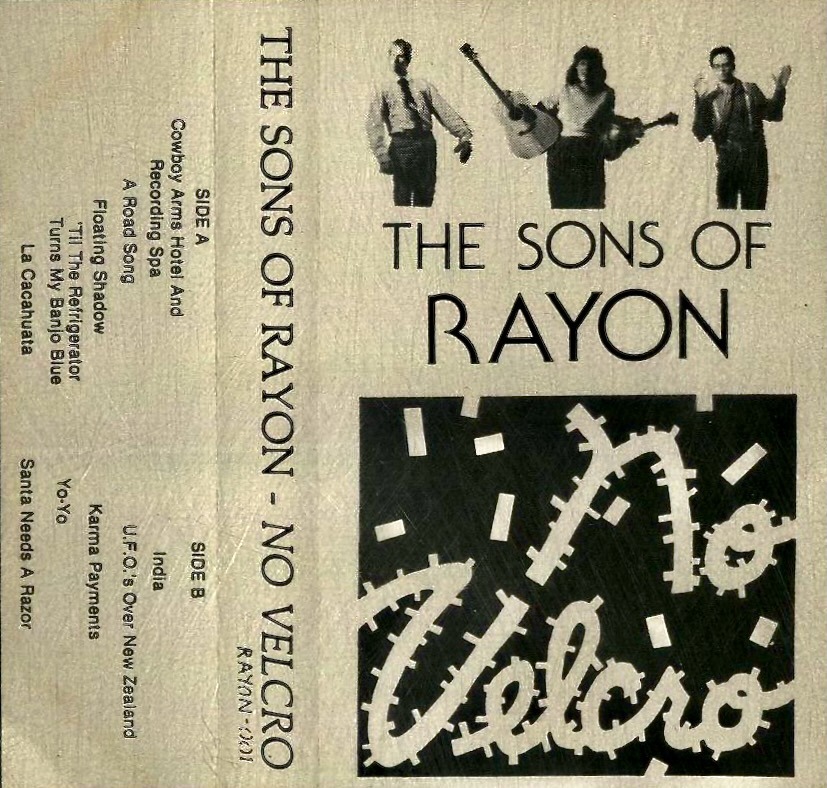

I have a cassette tape of the band that I’ve cherished for my entire adult life. One of my favorite Sons tunes was UFOs over New Zealand. The melody and lyrics stuck with me for more than 30-years until Paul finally agreed to let me do a cover of it with him singing. The concept of the song is perplexing; it muses about cowboys in outer space, Unidentified Flying Objects over New Zealand, and spaceships known to African Zulus. It was a Nerd-grass lover’s dream and would be the closest I would ever come to being one of the Sons of Rayon.

Paul and I worked on an arrangement of UFOs in 2007 as a proof-of-concept test for what would become our 2013 album Does Anybody Really Know What Time it is? (innova 864). That record was created by a musical collective under the sobriquet “Misfit Toys.” The band featured Paul on banjo and vocals, Matthew Wilson on drums and vocals, the late clarinet master, Robert Parades, on clarinet and vocals, some amazing guest performers, and me on everything else.

Unfortunately, the track didn’t make the cut as we pivoted the project to a collection of reimagined tunes from the 1970s. It wasn’t until 2017 that we revisited UFOs for a performance of Paul’s Strange Angels project in Iowa City. The track then went back into digital purgatory on a hard drive until I pulled it out again after his passing. The sound of his unique voice was solid, mature, and optimistic; his pitch is crystal clear and unaided by autotune. It gets me every time.

The Measure of Friendship

In remembering Paul over the last few weeks, I thought about the measure of a friendship. One measure might be someone who will compose a new centerpiece for every important moment of your career. Paul wrote music for so many events in my life including my Master’s recital (Verbum Salutis), a DMA recital (Prelude to the Blue and Perfumed Abyss), and many other important performances. He never wanted a dime for his commissions from me. He would say “just get me six performances” with which I dutifully obliged. I’ve performed his works at four universities, at the Percussive Arts Society International Convention, on new music concerts, and in venues from Kansas to Montana, Kentucky to Colorado, and North Carolina to New Mexico, not to mention more than a few performances at the University of Iowa.

Having a friend who will respond with an instant “yes, and” every time you utter the phrase, “here’s a crazy idea” is a blessing. Paul and I said “yes and” to each other for over forty years. Even in the last months of his life we continued talking about the “next” project. Paul was friends with a relative of one of the Brothers Gibb (you may know them as the BeeGees) who liked our Misfit Toys project and was interested in doing a “Misfit Toys plays the BeeGees” album with us. We talked about it again in the summer before he died. He still had plans to return to the University of Northern Colorado to teach his students and I suggested we start sharing demos for the BeeGees project while he was convalescing. He said he would try but was starting to “get kind of foggy.” I told him to do his best and that I loved him. It was the last time we spoke.

Paul was a great friend, and he visited us in every place Liesa and I lived since the day we met in Wichita. He would come, play the banjo, cook egg rolls, and even sleep on the floor amongst boxes in a bedroom not yet unpacked from a move to Lexington, KY. He travelled to Bozeman, MT with his lifelong friend Kelly Werts to perform his most famous work Edgard Varese in the Gobi Desert with me for the second of several times in my career. And he came to Iowa frequently to play music, make recordings, and plot our overthrow of the musical elite.

We once had a fun evening in our little town when having dinner in a darkened restaurant, Paul was mistaken for the actor Billy Bob Thornton. He relished the idea of being mistaken for a celebrity and played the part with gusto all evening. Paul was unfazed saying that this sort of thing happened to him all the time during his “Billy Bob doppelganger days.”

He simply added these fantastic happenings to our many shared experiences and filed them away as another facet of his fascinating life as an itinerate musician/composer.

But Paul had many other friends and musical collaborators just like me, and I was always jealous! Not really jealous. . .but yeah, kinda jealous. He had dozens of collaborations with musicians from around the world, and he wrote pieces for them as well. His musical DNA can be found in the repertoire of many musicians and ensembles throughout the world, and I expect his music will continue to live on, that is, if we have anything to say about it.

It is apropos that one of the last bands he performed with was called Multifarious, a jazz trio with friends Sue McKenzie playing saxophones and Susan Mayo on cello, to put a final exclamation point on his truly multifarious musical life.

Riffing on Hunter S. Thompson in a blog post from 2016, Paul wrote that “Improvising is sometimes like driving without headlights on backroads on a moonlit night”9 which translated means that “improvising is exciting but not always without risk!” One thing we’ve learned is that creative things aren’t without risk, but Paul wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Paul Iserman Elwood, composer and musician of Wichita, Kansas, September 21, 1958 — February 2, 2025, Marseille, France. Rest in Peace my friend.

One more thing before we go:

Musa Yelcin writing for the idea sharing website Medium (a home for human stories and ideas) writes that the African Zulus “are a mysterious society that stands out not only for their warrior identity but also for their deep connection with space.” They call themselves “Children of the Sky” and believe that their origin is in the stars. The post goes on to say that “The modern scientific world is also interested in the Zulu tribe’s extraordinary astronomical knowledge. It’s no coincidence that NASA has studied Zulu astronomy, and some archaeologists believe the tribe possessed ancient technological knowledge.” There are many tribal stories of “visitors coming with metal birds” and cave drawings resembling spaceships frequently encountered in Zulu legends that have caught the attention of “ancient astronaut” theorists. “Tribe members see the sky as the ‘home of ancestors’ and perform special rituals during every full moon,” and they consider meteor showers to be sacred.10 Just thought you might like to know where those crazy lyrics for UFOs Over New Zealand sprang from.

Oh, and another thing:

Composer, conductor, and teacher Edwin London might as well have been talking about Paul when in an interview with Bruce Duffie he said “I have always assumed, both in my own work and my own career and with others, that each of us has an individual voice within, and that if the world were a more hospitable place, everyone would have an opportunity to define their own voice, or to at least hear it, so that everyone would understand each other. As it is, many people get shut out of the process, and the artist is usually a one-minded-type individual who comes to the fore in a cultural situation as a progenitor of art. Maybe that is what art is for—that somehow, those who are obsessive enough or obsessed enough to continue working, to break through the barriers of inhibition in terms of their own work and their offerings, get a playing. Maybe it’s as simple as all that. Maybe they are metabolically suited to being artists and others aren’t.”11

Amen!

Citations:

1Thompson, Hunter S. Gonzo Papers, Vol. 2: Generation of Swine: Tales of Shame and Degradation in the ’80s, Summit Books, 1988, ISBN 978-0-671-66147-2

2Beaudoin, Jedd. Composer Paul Elwood Maintains Sense Of Mystery With ‘Strange Angels’, Interview for KMUW 89.1 FM, Wichita, Kansas, March 15, 2017

3Earle, Joe. Celebrating a Synthetic Heritage, The Wichita Eagle-Beacon, Wednesday, November 20, 1985

4Moore, Daniel P. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation: Confidential Report on Candidate for Fellowship Paul Elwood, author’s personal papers, December 11, 2023

5Moore, Daniel P. Conversation with JC and Karen Combs, Wichita, Kansas, November 13, 2021

6Moore, Daniel P. J.C. Combs and the Wisdom of Words and Wrestlers, blog post June 6, 2021

7Grainger, Don. J.C. Combs Has Done It Again: Percussion Professor Stretches Limits with Pop(corn) Music, The Wichita Eagle-Beacon, Lively Arts, Sunday, April 15, 1984

8Contributor. Sons of Rayon Promotional Material circa 1984, from the author’s collection

9Elwood, Paul I. The Dim and Dirty Road, Sound Choices: Paul Elwood, blog post, January 1, 2016

10Yalcin, Musa. The Children of the Stars: The Mysterious Space Connections of the Zulu Tribe, Blog post, The Medium:

11Duffie, Bruce. Composer/Conductor Edwin London: A Conversation with Bruce Duffie, bruceduffie.com, 1989

Other Sources: