If you are a percussionist, and you think about things way too much, as I apparently do, it might occur to you that the very idea of playing beautiful and compelling music on an amalgam of bits and bobs of wood and metal is something really quite absurd. If you aren’t a percussionist, or even a musician, you might feel the same way, therefore a little explanation might be of help to everyone involved.

Since the beginning of time, humans have desired to make and play musical instruments. Many consider the human voice to be the first musical instrument, yet there are differing opinions. In his book Drumming at the Edge of Magic, Grateful Dead drummer and writer, Mickey Hart gives his theory that “[i]n the beginning was noise. And noise begat rhythm. And rhythm begat everything else.” “Everything” in this scenario includes the rhythmic vibration of the vocal cords that produced speech and eventually singing. He goes on to say that “[t]his is a cosmology a drummer can live with. Strike a membrane with a stick, the ear fills with noise—unmelodic, inharmonic sound. Strike it a second time, a third, you’ve got rhythm.”

The oldest handmade musical instrument in the world is said to be a 60,000 year old flute made by Neanderthals (who else, would make a flute before a drum?). The National Museum of Slovenia, where it is housed, describes the instrument as being “made from the left thighbone of a young cave bear and has four pierced holes. Musical experiments confirmed findings of archaeological research that the size and the position of the holes cannot be accidental—they were made with the intention of musical expression.”

But how and why did humans come up with the idea of making music on inanimate objects in the first place? Maybe the people who invented musical instruments did so because they couldn’t sing? Or maybe not. For whatever reason, many of earth’s inhabitants are compelled to make music on instruments, and they search, tirelessly, to find or create the technique or the technology to make that happen. From Ctesibius of Alexandria’s creation of the organ in the third century BC, to Garage Band or Pro Tools today, musicians have looked to technology to help them make music.

The existential need for music making often compels humans to find ways to make music even in the face of oppression or poverty as in the case of the people of Trinidad and Tobago who created two musical instrument genres; tamboo bamboo, a form of music making using bamboo stalks cut to different lengths to accompany singing; and the National Instrument of Trinidad, the steel pan.

Musicians search for any type of conveyance into the ears (and hearts) of those who might hear their sounds and enjoy them. They hope to free the inner voice that is compelled to find a way to connect with its audience.

In the case of mallet percussion instruments, the notion that repeatedly striking a collection of tuned wooden planks, steel bars, or aluminum slats, with yarn-covered-balls-on-sticks, could create a pleasing musical sound seems ridiculous at best and futile at worst, yet as percussionists, we attempt to do it every day.

From the humble beginnings of mallet percussion, which includes the xylophones of Africa, the European Strohfiedel, and the marimbas of Central America, mallet players have attempted to amuse, entertain, and move their listeners with these simple instruments. In the 1920s, the xylophone was a novelty instrument that was often referred to by its zen-like nickname, “the woodpile.” Its repertoire was drawn from every type of music that captured the imagination of the performers. Playing music on a pile of wood (the essence of the xylophone) seems outrageous when you think about it.

Just playing a simple four-part chorale on a marimba is one of the most challenging things to perform, simply because the instrument was never meant to do such things. Attempting to produce the illusion-of-sustain by means of a tremolo (roll) can be a blister-inducing, frustrating, and exhausting experience for a marimba player.

When you further consider that playing anything on a mallet instrument other than idiomatic music is a stretch to begin with, things get even more dicey. For instance, who among us has the requisite birthright to play Bach? Well, depending on who you ask; practically no one! But we percussionists like to play Bach, as well as many other types of classical and non-classical music, that were never intended for the marimba, such as jazz or popular music.

So, if these things are so difficult to do, why bother? It’s simple; we are driven to do so.

It is often said that an instrument finds you, not the other way around. It has been said that you can force a child to choose the piano but very few will be chosen “by” the piano in return. I came to percussion almost completely by accident having fully intended to become the next Herb Alpert (the charismatic trumpet player and band leader of the 1960s). But that is a story for another day. Once an instrument chooses you, it soon becomes your passion to play on it the music that speaks to you—it becomes a musical imperative.

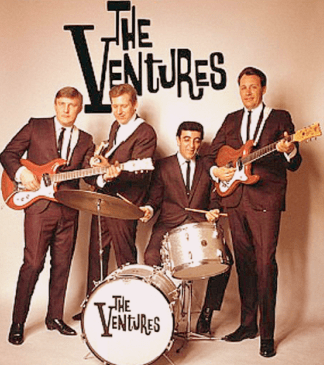

I’m a big fan of instrumental musicians who take on different types of music and recast it in their own image. Musicians such as Bill Frisell, Jake Shimabukuro, Dick Schory and the Percussion Pops Orchestra, and the Ventures (arguably, the best-selling instrumental Rock band in music history) have all inspired me in different ways.

The Ventures were a guitar based group of the 1960s (and beyond) who were famous for their numerous and varied recordings. When inducting them into the 2008 class of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, presenter John Fogerty said “the Ventures have gone on to record over 250 albums. Now days some of us would be happy to sell 250 albums.”

The Ventures philosophy was that if you were going to do an instrumental cover of someone else’s tune, then you needed to find a way to make it sound like a completely new composition. In their words, it had to be “Venturized.” As much as 90% of the music they recorded were covers of other people’s music. But the covers were so creative, and in many instances so different from the original, that most people thought they were the band’s original compositions. Their biggest hits such as Walk, Don’t Run, Wipeout, Hawaii 5-0, and Pipeline were all covers!

Hawaiian ukulele artist Jake Shimabukuro plays a repertoire that ranges from classic Hawaiian folk songs to his original compositions, and covers of the music he grew up listening to. He famously performs a version of Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody on ukulele. Jake also cleverly reimagines music from Michael Jackson, George Harrison, and others, and you can hear in his performances how much he loves and respects this music. He says “my mother taught me three chords on the uke and I was “hooked.” He was chosen by the ukulele. Then, he set out to imbue the music he loved with his own vision. He does things with the ukulele that the ukulele was never meant to do. Right On!

The Britain Moore Duo (BMD), my steel pan and marimba duo of the last 35 years, also tends to work from covers of other people’s music—often against the advice and admonishment of our mentors. We call our covers “BMD Treatments.” One of our most popular covers is of the Gershwin classic Summertime. We used an Afro-Caribbean 12/8 groove and then curiously never played the melody of the tune until the final chorus, which always causes a few head tilts from the audience.

But loving a piece of music and being able to make it sound good on your own instrument can be a problem. How do you know if it will work? Sometimes a performer’s love for a piece of music blinds them to the reality that they are unable to capture the essence of it on their instrument.

I am lucky to be in a position in my performing career that my repertoire has evolved to include only the music that speaks to me personally. Along the way I have developed a sort-of litmus test to determine if a piece of music I love can be translated to the instruments that have chosen me (those absurd mallet percussion instruments).

The Composer Test:

If a composer were to hear you performing their composition, would they think you were mocking it? Would Mozart be insulted by your performance or would he be inspired to run home and write a new piece for you and your instrument? Think about how you would feel about your version if the composer was sitting in the audience.

What about vaudeville, parody, and humor in music? There are lots of examples of arrangements that are meant to be funny takes or send-ups of otherwise serious music. In this case, you just have to play it flawlessly and then hope that the composer has a good sense of humor.

Inventory:

To begin, a quick inventory of the notes and essential elements will tell you if you have what you need to perform a piece of music that you love. Even if the answer is no, there are ways to make things work. In classical or contemporary music, it is possible to do some note reassignments or octave shifting as long as the general direction of a line is not interrupted by doing so. I personally don’t mind transposing entire pieces (although some of my colleagues take issue with that practice).

The ukulele version of Jake Shimabukuro’s Bohemian Rhapsody has some pretty cool note reassignments but the inventory of notes and essential elements of the original are all there, lending themselves to the creation of an imaginative rendition of a ubiquitous song.

Listen, hear, and embrace:

It should go without saying that one should always listen to how your music sounds, however, we can get so caught up in the process of invention that we might be listening without really “hearing.” We continue to hold the original version of the music in our heads and not listen critically enough to our own interpretation.

It can be a difficult admission to realize that we are simply unable to make a particular piece of music sound good—at least not yet. Perhaps a few more years of practice and a little more musical maturity will make the difference the next time around. This has happened to me on many occasions (also a story for another day). But if you try and fail, it’s OK, because as Herb Alpert would say, “the beauty of music making isn’t in attaining perfection because you can never get there. That’s the seductive part of it.”

It is important to embrace the true sound of your instrument which includes both the instrument’s advantages and disadvantages. But this can only be done with honest critical listening to how you and your instrument sound today, and by asking yourself if your arrangement is transcendent.

Does it transcend?

Audiences have different reactions to hearing music performed out of context. If I play a pop song on the marimba or vibes, some in the audience will recognize a familiar tune immediately. If I play a standard song like Moon River, someone might indicate their recognition with a knowing laugh or a soft “ahh.” Others will simply enjoy the arrangement and be attracted to the sound but will come up after the show and ask, “what was the name of that song you played?” Taken out of context and without the words, a good arrangement should transcend the original and become something both familiar and new, just as the Ventures tried to do. Simply put, does your version have its own intrinsic beauty that transcends the original? Does it need the lyrics in order to be meaningful? In many cases, the answer is no. Again Herb Alpert hits it out of the park, when he says “people don’t listen with their ears, they listen with their soul.”

So, I encourage you to continue to pursue the music that is in your head and in your heart regardless of how crazy it may seem because, as M. C. Escher wrote; “Only those who attempt the absurd will achieve the impossible.”

Here is a playlist of some of the covers that I’ve enjoyed creating:

Citations:

Drumming at the Edge of Magic: a Journey into the Spirit of Percussion

Mickey Hart with Jay Stevens and Fredric Lieberman, Harper Collins, 1990

National Museum of Slovenia

https://www.nms.si/en/collections/highlights/343-Neanderthal-flute

Classic History: The History of the Pipe Organ,

http://www.classichistory.net/archives/organ

Herb Alpert Is (documentary film)

https://www.herbalpertis.com

I really enjoyed this passage back into time with you Daniel. You are a true talent and a life long student of music. Hope to see you and Liesa at our get it together in September.