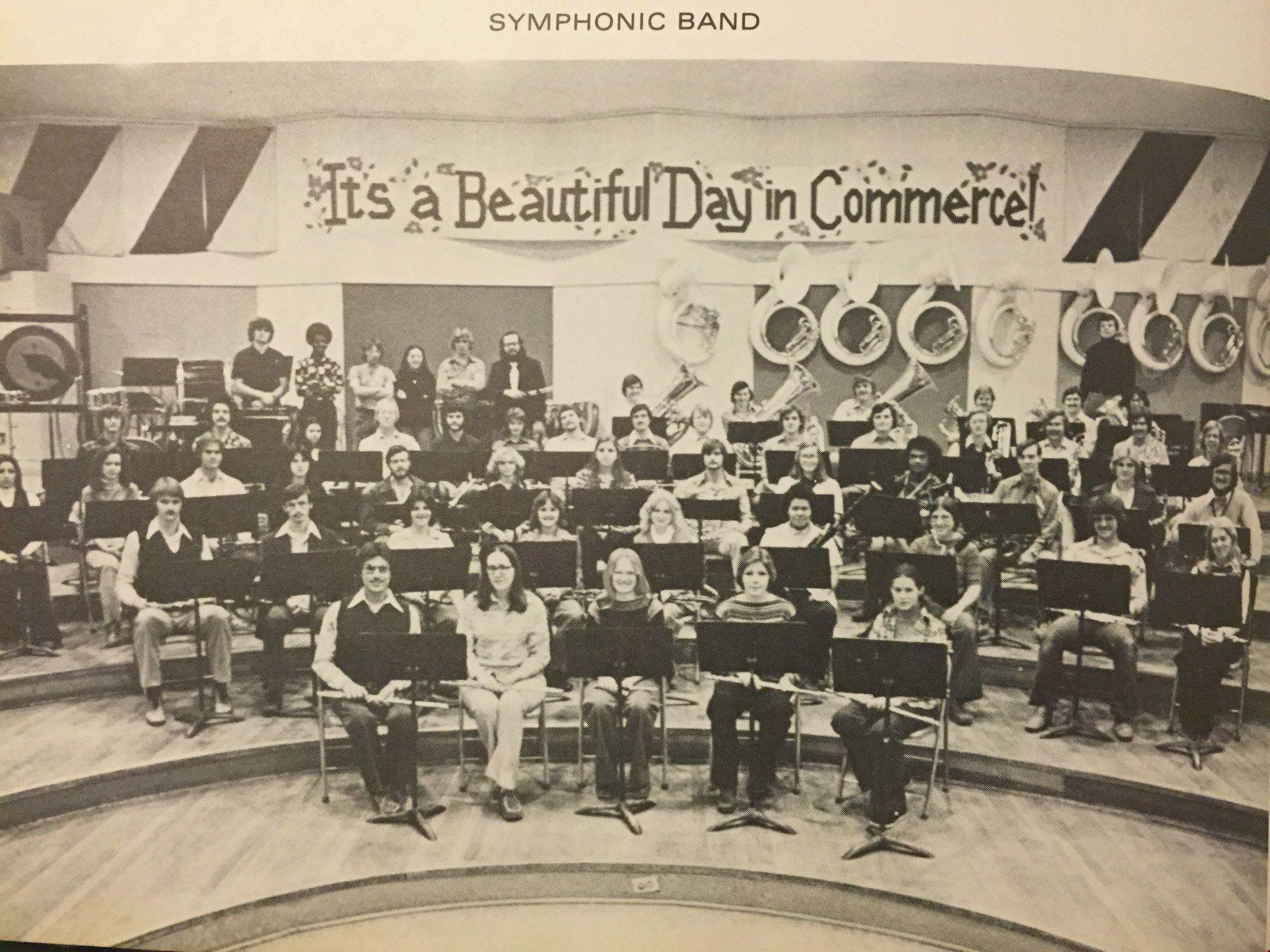

The first thing a person might notice upon entering the music rehearsal room at East Texas State University in 1976 was a large, brightly colored banner proclaiming “It’s a Beautiful Day in Commerce!” Over the years, mystery and lore came to surround the whimsically hand-lettered sign. No one seems to know who created it or how it got there.

Conflicting reports about when the banner first appeared are also in abundance. ETSU Music alumnus Toppy Hill recalls that “the banner first appeared in about 1972.” However, storied Music Professor and most-feared instructor of Music Literature, Gene Lockhart, recalled that his “first ‘intimate’ classes of Arts & Humanities 303 (100 to 150 strong) were taught in the band room in 1969. It was appropriately bedecked with folding chairs, raked seating and ‘The Sign’ on the south wall.”

While there is plenty of intrigue about the three by twenty-foot banner, one thing is certain: how the phrase originated.

Much has changed in Commerce since my college days in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1995 the school name was changed from East Texas State University to Texas A&M University Commerce, and in 2011, the original, well-worn music facility was replaced with a beautiful gateway building overlooking Gee Lake on one side and Memorial Stadium on the other. Then somewhere along the way—after numerous transmogrifications of the old building—the Beautiful Day in Commerce banner faded into memory along with Good Old ET.

In 1957—long before the banner made its debut—Dr. Neill H. Humfeld made his entrance at ETSU where he taught trombone and served as director of bands (1962-1972). A fresh recruit from the Eastman School of Music, he was one of the nation’s top trombonists, an inspired educator, and a remarkable human being by any measure. Many trombonists today would be honored to receive the “Neill Humfeld Award for Excellence in Trombone Teaching” from the International Trombone Association.

In those days, the music faculty at ET took a wholistic approach to education. A major professor guided your development but you might also be coached by the trumpet professor on how to play brushes on a ballad, you could be called out for your etiquette by the clarinet professor, or admonished to learn your scales and chords by your class piano teacher—in the hallway. I shudder to even think about what might happen should you miss too many questions on Lockhart’s Music Lit pop-quizzes. Although I was a percussionist, Dr. Humfeld was my academic advisor during my first few years at ET. Along the way, he kept me out (or got me out) of trouble on numerous occasions.

Chris Clark, trombonist with the “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band, recalled that as a high school student, many of his lessons with Dr. Humfeld began with the phrase “it’s a beautiful day in Commerce.” In fact, anyone who ever knew Dr. Humfeld likely received the same greeting at some point. “It was one of Neill’s favorite sayings” Lockhart added. It was his catch phrase but it was more than that; it was an affirmation intended to remind the hearer that beauty is more about how you perceive things than how they may appear.

In the 1970s, Commerce, Texas—formerly known as Cow Hill—was in decline. What began as an optimistic center of commerce for the East Texas Cotton Industry (thus the name), had long since fallen on hard times. Neither the town nor the university campus were picture postcard destinations by any stretch of the imagination, and many professors began to take flight from Commerce in the late 1980s. Some thought the banner might be an ironic statement about the “beauty” of Commerce itself.

Dr. Humfeld certainly wouldn’t have intended that meaning of the phrase. ETSU professor of clarinet, Dr. James Deaton, Humfeld’s lifelong friend, collaborator, and comedic accomplice, remembers seeing a motto in a colleague’s office that said “‘bloom where you are planted.’ I know that Neill’s ‘beautiful day in commerce’ sign meant the same thing, ‘attitude is important’. It means look for the positive things in life.”

Another apocryphal story I was told as a starry-eyed freshman was that Dr. Humfeld coined the phrase as encouragement to the marching band to keep rehearsing in the rain before a big football game performance. But his daughter Nancy Jo recalled that “it had absolutely nothing to do with the weather—it was about your mindset.” Chris Clark agrees. “Dr. Humfeld’s statement really reflected, to me, his core value as a teacher; to always stay positive, and to teach his students that they were much more than just a musician.”

So, what’s the big deal? It’s just a sign; a stunt perpetrated by one of the music fraternities or sororities, or perhaps by some of those snarky misanthropes who hung out in the student lounge* all day. If that were the case, wouldn’t the banner simply disappear after homecoming or when a new band director took over? It probably should’ve, but still it remained. Dr. Deaton doesn’t remember how or when the sign was made either but he suspects there was some student “help” in the process. He said “I do know that the sign and the attitude it conveys has its own life now.”

*During my time at ET the student lounge was dubbed the “Lizard Lounge” by director of bands, James Keene. One might infer the meaning of the phrase.

The banner and the symbolism seemed to bind us together into the legacy of ETSU, which may account for why many of my generation had a difficult time letting go of Old ET. But to help put things into perspective, a former TAMUC President once told me that there are “far more TAMUC graduates today than there ever were from ET.” Point taken.

The many amazing people who sat under that banner went on to successful careers as leaders in music education, performance, and in many other walks of life. I’m sure this is still the case at TAMUC but perhaps today’s students are connected in different ways—by a new talisman—or could some small trace from the past still remain?

Dr. Humfeld’s affirmation not only inspired several generations of music students, it ultimately transcended the walls of the music building and weaved its way into the fabric of the university. Professor Jimmy Clark, Dr. Humfeld’s former student and successor, wrote that “his quote is still used by a lot of people!”

In 2015, nearly 25-years after Dr. Humfeld’s passing, Dr. Adolfo Benavides, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, announced that TAMUC had been classified as a Research 2 institution*. He went on to say that “to be among the select group of 107 universities in the United States is, indeed, quite an honor. What a fantastic way to begin writing the history of our next 125 years as one of the leaders in Higher Education—yet another beautiful day to be in Commerce, Texas.”

“Well roared, Lion!” as the Bard would say.

*The R2 designation by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education represents the second highest tier of research activity at a Doctoral granting institution.

When I asked about the possible whereabouts of the banner, professor Jimmy Clark exclaimed “I have it! It’s in our son [Chris’s] bedroom.” (Master Gunnery Sergeant Clark didn’t even know that one)

Percussion professor and current Department Chair, Dr. Brian Zator, remembers the banner being in place “until a few years before the move to the new building.” He added “I have a small wooden sign in my new office with the saying.” Well, the more things change, the more they stay the same, I suppose!

Perhaps the current students of A&M Commerce continue to be inspired in some way by Dr. Humfeld after all.

Professor Humfeld never retired from ET. He fought a long and valiant battle with cancer and died in October 1991 while “still on the payroll,” as professor Clark told me, “they hired me as an adjunct to teach for him in late summer but he was not able to start the fall semester.”

Nancy Jo recalled that her father “felt that you should always keep a positive attitude no matter what the weather or your circumstances. It was that mindset that allowed him to live twice as long as someone with his prognosis would have normally.” Dr. Deaton wrote “I know that is what it [the banner] meant to Neill because I remember when he was dying with cancer. He NEVER complained, never lost his sense of humor, and was always concerned about others.”

Dr. Humfeld just wanted to continue to make music for as long as he could. Dr. Deaton noted that despite being in pain “he continued to lead the church choir and never ever cut rehearsals short.” His final performance was a trombone trio with his students Jimmy and Chris Clark at Commerce High School, Deaton remembers, “when he was so ill he couldn’t carry his trombone out to the stage.”

Yes, it is always a beautiful day in Commerce, or Iowa City, or wherever you happen to find yourself, just as long as you have the right attitude and remember to “bloom where you are planted.” Good advice. Thanks for everything Dr. Humfeld!

Dan Moore, Class of 1981

I wonder if there are other stories out there about how the banner inspired you, or if anyone knows more about its origin? I’m sure the statute of limitations has expired.

Do you have a story about Dr. Humfeld? Feel free to leave a comment below. Corrections, annotations, amplifications, or humorous asides are welcome.

Special thanks to the kind folks who contributed to this post: Nancy Jo Humfeld, James Deaton, Gene Lockhart, Jimmy Clark, Chris Clark, Toppy Hill, Sheila Howell Ratcliff, and Brian Zator.